State-owned enterprises

State-owned enterprises have historically played an important role across the EBRD regions. Today, they account for almost half of all public-sector employment. In many economies, state enterprises have more or less disappeared from the manufacturing sector over the last 20 years or so. However, they remain important providers of energy and (often subsidised) services such as railway transport and municipal utilities. They are often tasked with providing such services to poorer and more remote sections of the population, especially in countries with limited capacity to involve the private sector in the provision of public services. State enterprises can also act as automatic stabilisers when faced with adverse economic and technological shocks, providing more stable sources of employment during downturns and in economically disadvantaged regions. However, significant challenges remain when it comes to improving the corporate governance of such enterprises.

Introduction

State-owned enterprises have historically played an important role in the EBRD regions, both in post-communist economies and in the southern and eastern Mediterranean (see Box 2.1). While state enterprises still account for almost half of all state employment in those economies (with the other half comprising employment in the broader public sector – including education, healthcare and public administration), their role has changed considerably since the 1990s.

The rationale for state ownership

State intervention to address externalities

There are various reasons why a government might want to establish and maintain state ownership.3 A state presence is often justified, for example, by the need to address market failures – for instance, in natural monopoly scenarios and network industries, where a privately provided service could be incomplete or inadequate, or on account of significant externalities.

Alternatives to state ownership

In most of these cases, state intervention need not necessarily take the form of state ownership of enterprises. Services such as rail transport or broadband can be provided by private companies, with government subsidies and public service obligations ensuring universal coverage. Poor households facing large utility bills can receive targeted means-tested benefits. The state can lean against rising regional disparities through fiscal transfers, targeted investment and other industrial policy measures (see Chapter 1). Well-designed social safety nets can act as automatic stabilisers in the face of economic and technological shocks. And environmental objectives can be pursued through regulation and taxation.

State enterprises are more prevalent where administrative capacity is lower

For these reasons, state-owned enterprises tend to play a somewhat greater role in countries with more limited administrative capacity (see Chart 2.1). In countries with sufficient administrative capacity, alternative policies such as targeted social safety nets and public service obligations are often preferred, given the concerns about the inefficiencies and weak governance of such enterprises. Where administrative capacity is lacking, state enterprises may be seen as a suitable second-best policy choice. For instance, while low-productivity employment in the public sector may be costly for the taxpayer and the economy, an alternative that involves persistently high unemployment in a region that is lagging behind economically may be associated with even greater long-term costs. Those costs extend beyond the direct impact on individual households and include long-term externality costs caused by rising inequality and the erosion of social cohesion and trust. As noted in Chapter 1, differences in citizens’ preferences across societies may also help to shape the landscape in terms of the role that state-owned enterprises play in the economy.

Source: Global Findex Database, UN DESA, World Bank and authors’ calculations.

Note: The administrative capacity index takes account of a measure of e-government (which looks at the scope and quality of online services, the development of telecommunication infrastructure and inherent human capital), a Worldwide Governance Indicator measuring the effectiveness of government, a Doing Business indicator assessing the distance to the frontier and an indicator measuring the routine use of bank accounts by the country’s population. See Box 1.5 for details.

State-owned enterprises: a portrait

In the mid-2010s, the state accounted, on average, for about a quarter of total employment in the EBRD regions (see Chapter 1), of which around 44 per cent was accounted for by state-owned enterprises (based on the results of the 2016 round of the Life in Transition Survey). The contribution made by state enterprises was particularly large in Azerbaijan and Belarus, whereas the broader public sector (areas such as education, healthcare and public administration) accounted for the bulk of state employment in Turkey, Cyprus, Greece and the southern and eastern Mediterranean (see Chart 2.2).

State-owned enterprises are concentrated in the transport and utility sectors

While sectoral data for the early years of the transition process are scarce, state enterprises in the early 1990s were typically manufacturers (operating large plants in heavy industries, for instance). This picture has changed significantly, with many of those manufacturing firms being privatised or going bankrupt. Analysis based on a unique OECD dataset examining the sectoral composition of state-owned enterprises suggests that by 2015 those enterprises were concentrated in the transport and public utility sectors, often being owned locally rather than centrally (see Chart 2.4).4 In the eight EBRD economies covered by the OECD database (Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia and Turkey), transport, electricity, gas and other utilities account for a combined total of 69 per cent of employment by state enterprises. This is similar to the picture observed in a sample of advanced economies. In comparator emerging markets (Argentina, Brazil, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, India and Mexico), state enterprises continue to play a more important role in primary sectors and manufacturing. This suggests that state enterprises’ shares of competitive sectors – those where concerns about the unfair advantages of state ownership distorting the level playing field are the strongest – may be falling.

More state-owned manufacturers in lower-income economies

That being said, notable exceptions remain, with state enterprises remaining present in competitive sectors in some higher-income economies in the EBRD regions (such as the Hungarian, Polish and Slovenian chemical and pharmaceutical sectors). Meanwhile, the results of the Life in Transition Survey indicate that state enterprises are also still playing an important role in the manufacturing sectors of poorer countries (see Chart 2.5). Indeed, in Azerbaijan, Belarus and some countries in Central Asia, state enterprises account for 30 to 70 per cent of total employment in manufacturing, compared with less than 10 per cent in most of central Europe and the Baltic states (an estimate that is consistent across both OECD and LiTS data).

The rise of state-owned multinationals

Increasingly, state enterprises are also playing an important role at international level. National oil and gas companies, for instance (such as Rosneft and Gazprom in Russia), are often listed on major stock exchanges and operate internationally in ways that are similar to their private-sector counterparts.

Data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) indicate that there are around 1,500 large state-owned multinationals in the world, which represent just 1.5 per cent of all multinational enterprises but own about 10 per cent of all foreign affiliates and account for around 10 per cent of global greenfield investment.5 In contrast with their private-sector counterparts, state-owned multinationals are heavily concentrated in natural resources and financial services (with the EBRD regions being no exception in that regard). In the EBRD regions, their ranks also include construction and engineering firms, as well as chemical firms and manufacturers of fertilisers.

Source: Life in Transition Survey 2016, ILO, OECD and authors’ calculations.

Note: These estimates are based on the answers of primary respondents in the Life in Transition Survey (except in the case of Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia, where estimates are based on ILO and OECD data).

Source: Life in Transition Survey 2016 and authors’ calculations.

Note: These estimates are based on the answers of primary respondents in the Life in Transition Survey.

Source: OECD and authors’ calculations.

Note: These estimates are based on an OECD dataset on the size and sectoral composition of countries’ state-owned enterprise sectors in 2015. “EBRD regions” refers to Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia and Turkey. “Other emerging markets” refers to Argentina, Brazil, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, India and Mexico. These estimates only include enterprises that are engaged in economic activities in the marketplace, excluding entities that primarily perform a public policy or administrative function. “Market value” is defined as market equity for listed state enterprises and book equity for unlisted enterprises.

Source: Life in Transition Survey 2016 and authors’ calculations.

Universal provision of affordable services

State enterprises pursue a wide range of objectives besides the maximisation of profits, with particular emphasis being placed on the universal provision of services at affordable rates. In a recent IMF survey, 90 per cent of governments in central, eastern and south-eastern Europe reported that their state enterprises had objectives relating to the provision of specific public goods and services.6 Similarly, state-owned banks may pursue non-commercial objectives, such as increasing financial inclusion or improving access to finance for specific groups of customers (as discussed in detail in Chapter 3). This section looks at state enterprises providing transport services, utilities and broadband.

Railway companies: maintaining a service on unprofitable lines

In most countries, railways have traditionally been run by monolithic vertically integrated entities, with those entities providing infrastructure, passenger and freight transport, and various related services. However, demand for reform has increased over the years, with a view to improving railways’ efficiency and financial sustainability, reducing the burden on government budgets and increasing the competitiveness of rail travel relative to other modes of transport.

Municipally owned utilities: targeting universally affordable services

Many municipal services in the EBRD regions are provided through state enterprises, which are often owned by local governments. As in the railway sector, universal access to affordable services is seen as an important economic policy objective, with lower-income households spending a larger percentage of their income on utilities. Evidence from the latest round of the Life in Transition Survey suggests that people in the poorest income decile in the EBRD regions spend more than a fifth of their income on utility bills – a significantly higher percentage than their counterparts in advanced economies.

State intervention to ensure universal broadband services

In most economies, the quality of broadband coverage in rural areas lags behind that seen in urban areas. In the EU, for example, only 88 per cent of rural households had access to broadband in 2018, compared with an average of 97 per cent across all households. That gap was more pronounced in central and south-eastern Europe. For instance, while 80 per cent of all Polish households had fixed broadband coverage in 2018, the figure for the country’s rural households was only just over half (see Chart 2.8). Such gaps have become even more problematic in the context of remote schooling and remote working during the Covid-19 pandemic, as discussed in Chapter 1.

Source: ILO, companies’ annual reports, national regulatory bodies and authors’ calculations.

Note: All data in this chart relate to state-owned railway companies and joint ventures (with the exception of data for the United Kingdom and Germany). Data for the United Kingdom relate to 2019, rather than 2018. Hungary and Lithuania also have independent train path allocation and infrastructure-charging bodies (not included here). As of 2019, Lithuania has a holding structure with limited guarantees of independence.

- Economies in the EBRD regions

- Other economies

Source: European Commission.

Note: The vertical axis measures the percentage of the costs arising from public service obligations that are recovered through passenger fares. The horizontal axis measures network utilisation as the total number of kilometres travelled by trains for every kilometre of track. There are no data on cost recovery for France or Slovenia.

Source: European Commission.

Other objectives: leaning against rising regional disparities

Technological changes have been reshaping the geography of production and the skill-sets that are demanded in labour markets. In that context, the economic importance of large cities has been increasing even faster than their share of the population. Conversely, many smaller cities, particularly those that are far from other urban agglomerations, have seen their local economies shrink and their populations decline. This has led to rising income disparities across regions within individual economies.15

State employment as a way of supporting disadvantaged regions

State employment can also be used as a way of supporting economically disadvantaged regions. In the United Kingdom, for example, HM Revenue and Customs has opened offices in Liverpool, the Department for Work and Pensions has offices in Newcastle, the Office for National Statistics has offices in Newport, and parts of the BBC – a state-owned broadcaster – moved to Salford in Greater Manchester. Similarly, the German government moved various public bodies east after reunification. More recently, the German state of Bavaria launched a large regional development programme, with more than 50 public bodies either moving to rural parts of the state or being established from scratch in those areas. Meanwhile, Denmark has moved thousands of government jobs to scores of different cities; Norway has moved its competition authority to Bergen, moved the Norwegian Polar Institute to Tromsø in the far north, and moved the Norwegian peace corps (Norec) to the small town of Førde; and South Korea has moved two-thirds of its government agencies away from Seoul (many of them to the newly built Sejong City). And in 2012 Georgia moved its parliament to Kutaisi, although that move has since been reversed.

More state employment in smaller towns and rural areas

The results indicate that state enterprises are more likely to be located in smaller cities than private firms (see Chart 2.9). In the EBRD regions, 44 per cent of state-owned enterprises are located in towns with fewer than 50,000 inhabitants, while only 13 per cent are found in cities of over a million. In contrast, only about a third of private firms are found in towns with populations below 50,000, while 22 per cent are located in cities of over a million. This pattern could, in part, reflect a legacy of central planning, under which secondary cities were consciously promoted and some state enterprises were sited without due regard for transport costs, as well as the fact that private investment is concentrated in large cities, benefiting from the presence of a large pool of highly skilled workers and a diverse range of customers and suppliers.

Residents of rural areas are more likely to regard the state as having primary responsibility for the creation of jobs

In line with those patterns, residents of rural areas also expect more from the state in terms of job creation. A survey conducted by the Austrian National Bank (OeNB) in 10 countries (nine of which are in the EBRD regions) asked respondents who they thought had primary responsibility for providing people with work. In the nine EBRD economies, almost half of all respondents living in rural areas thought the state should have primary responsibility for providing employment, compared with only 37 per cent of those living in capital cities. That difference remains statistically significant when controlling for individual characteristics such as age or education (see Chart 2.11 and Box 2.4).

Source: Enterprise Surveys and authors’ calculations.

Note: The Enterprise Surveys do not cover firms that are 100 per cent state-owned. In this chart, “state-owned” is defined as a firm where the state owns more than 50 per cent. These data represent simple averages. Very similar patterns are observed when using median eligibility sampling weights.

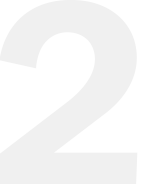

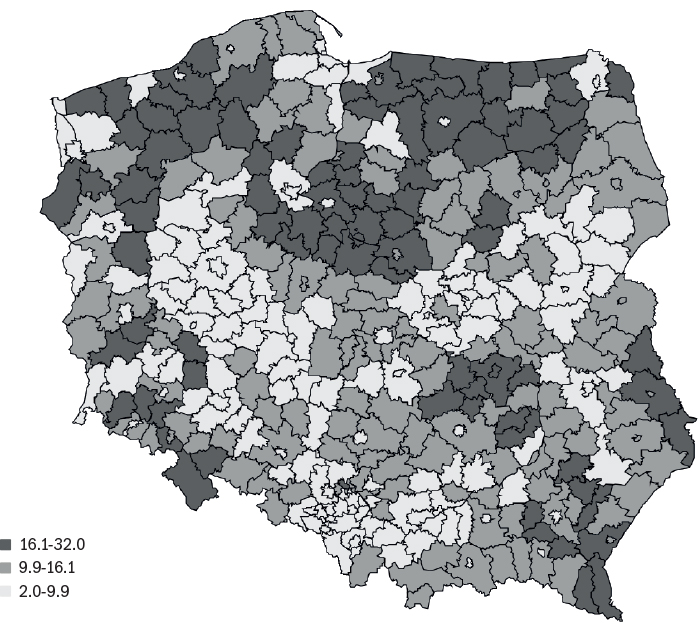

Source: National Statistics Poland and authors’ calculations.

Note: In the lower panel of this chart, “state employment” is defined as employment by a public-sector entity that is more than 50 per cent state-owned. Dots denote powiats in which industry accounts for a high percentage of employment.

Source: OeNB Euro Survey and authors’ calculations.

Note: Shares are weighted using census population statistics for age, gender, region, education and ethnicity (by country), before calculating simple averages across Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, North Macedonia and Serbia. Respondents who replied “don’t know” or declined to answer are excluded.

Public-sector employment as an automatic stabiliser

Over the longer term, as discussed in Chapter 1, there has been an increasing tendency for the state to take on the role of insurance provider, establishing a safety net to protect against things like unemployment, ill health and disability. Recently, however, technological changes have been shifting some risks back onto individuals, with fewer permanent contracts, more subcontracting, the rise of the gig economy and more zero-hours contracts. The people who have been most affected by these developments are actually those who are least willing or able to tolerate risks – those with lower levels of income and education. Partly as a reflection of this trend, support for the expansion of public ownership has been rising, as public-sector employment is commonly regarded as a less risky choice, with more risk-averse individuals being more likely to work in the public sector.

Public-sector employment responds less to the business cycle

There is a large body of literature showing that the investment and employment levels of state enterprises are typically less responsive to changing external conditions than those of private firms.18 Similarly, Chapter 3 shows that state-owned banks tend to be more stable lenders during crises. During the global financial crisis, for example, job losses and wage cuts at state-owned firms were smaller than they were at private firms.19 The EBRD’s new survey of the legal frameworks governing state enterprises, which is discussed in the last part of this chapter, reveals that as many as a quarter of all economies in the EBRD regions explicitly restrict the dismissal of state enterprises’ employees, over and above the job protection rules applicable to the private sector.

Public-sector employees less affected by the global financial crisis

Evidence from the Life in Transition Survey further corroborates these findings. Only 65 per cent of survey respondents who work for private firms in the EBRD regions have permanent contracts, compared with 82 per cent of people working for state enterprises (see Chart 2.12). Moreover, the crisis module in the 2010 round of the Life in Transition Survey also showed that public-sector employees were less likely to lose their job or experience delays in the payment of wages during the global financial crisis. These differences remain statistically significant when account is taken of individual characteristics such as age or gender, the size of the firm, and the sector and country of employment.20 The employees of state enterprises and other public entities are also more likely to be satisfied with their jobs and less likely to want to move, even after controlling for household income, and they also trust the government more.

Public-sector employees less affected by the Covid-19 crisis

Early evidence also seems to suggest that, so far, people employed by the state have been more shielded from economic hardship during the Covid-19 crisis.

Trade-off between risk and growth

Thus, state enterprises can act as automatic stabilisers in the face of adverse economic shocks, providing more stable employment and income. To the extent that various well-documented inefficiencies in state enterprises lead to lower levels of innovation and weaker productivity growth, this points to a trade-off between risk and growth.

State enterprises innovate less

Evidence from the latest round of Enterprise Surveys confirms that state enterprises are indeed less likely to adopt new products and processes or invest in research and development (R&D) than similar private-sector firms (see Chart 2.15).21 These effects are large, with state enterprises only about half as likely to innovate as comparable private-sector firms. Similarly, Chapter 3 shows that enterprises that borrow from state-owned banks are less likely to innovate than those borrowing from private sector banks. While the state has a major role to play in supporting innovation,22 majority state ownership of enterprises and banks may not be an effective instrument for providing such assistance. Innovation can instead be supported by providing subsidies and grants for R&D, funding basic research, promoting effective links between public research institutions and the private sector, facilitating the supply of specialised skills and specialised finance and supplying high-quality information and communication technology infrastructure.

- Employment in a state enterprise relative to private-sector employment

- Other public-sector employment relative to private-sector employment

Source: Life in Transition Survey 2016 and authors’ calculations.

Note: These estimates are derived from logit or ordered logit models with country fixed effects and country clustered standard errors. The sample is restricted to the EBRD regions. A coefficient larger than 1 suggests that being employed by a state enterprise or another public-sector entity increases the likelihood of the listed outcome relative to being employed in the private sector. Darker colours denote effects that are significant at the 5 per cent level. Regressions control for age, gender, marital status, urban/rural location, education and father’s education.

Source: Life in Transition Survey 2016, Google trends and authors’ calculations.

Note: The vertical axis measures changes in the volume of Google searches over the 18 weeks starting on 22 March 2020 relative to forecasts based on previous trends. State enterprises’ share of total employment is estimated on the basis of the answers given by primary respondents in the Life in Transition Survey.

- Economies in the EBRD regions

- Other emerging markets

- ▲ Advanced economies

Source: Global Findex Database 2017 and authors’ calculations.

Note: The required amount of emergency funds varies depending on the economy’s income per capita, ranging from US$ 50 in Tajikistan to US$ 1,100 in Slovenia.

Source: Enterprise Surveys and authors’ calculations.

Note: The Enterprise Surveys do not cover firms that are 100 per cent state-owned. In this chart, “state-owned” is defined as a firm where the state owns more than 50 per cent. However, the results are also robust to defining state-owned enterprises as firms where the state owns more than 25 per cent. Relative risk ratios are based on logit regressions, controlling for the logarithm of firm age, the logarithm of employment, city size, sector and country fixed effects, and whether the firm has a board or a business strategy. These estimates are derived from unweighted regressions, with similar results being obtained when using median eligibility sampling weights. A coefficient smaller than 1 suggests that state-owned enterprises are less likely to adopt the relevant measure than a private-sector firm. Darker bars denote effects that are significant at the 5 per cent level on the basis of country clustered standard errors.

State ownership as a climate policy tool?

Some of the world’s largest public companies are state-owned energy firms. This is increasingly giving rise to the question of whether state-owned enterprises could be used directly to support the transition to a green economy. Indirectly, the prevalence of state energy firms could potentially make it easier to overcome opposition to environmental regulations on the part of powerful (private) lobbies. At the same time, a few recent studies have highlighted state enterprises’ greater environmental engagement in certain contexts and their importance for investment in renewable energy.23

Winding down sunset industries: the example of coal

National governments and state enterprises are major players in fossil fuel markets. A few years ago, it was estimated that governments and state entities owned roughly 70 per cent of global oil and gas production assets, and around 60 per cent of the world’s coal mines and coal power plants.24 Moreover, the International Energy Agency (IEA) recently estimated that a group of 50 state enterprises in the power, oil and gas, iron and steel, and cement industries accounted for a combined total of more than 4 gigatonnes of greenhouse gas emissions in 2013 (CO2 equivalent) – more than the national greenhouse gas emissions of all countries except the United States of America and China.25 Against that background, this section looks specifically at state enterprises in the coal sector.

State enterprises as energy giants: the example of national oil companies

National oil companies (NOCs) produce approximately 55 per cent of the world’s oil and gas and control up to 90 per cent of global oil and gas reserves.30 They manage multi-billion-dollar portfolios of public assets, account for large percentages of government revenue, employ tens or even hundreds of thousands of people and make large investments in infrastructure (see Chart 2.19). A single NOC can account for more than 1 per cent of a country’s total employment. In some cases (such as SOCAR in Azerbaijan), their revenues even exceed the country’s GDP. Transfers from NOCs to national governments in the EBRD regions range from 2 to 18 per cent of total general government revenue (see Chart 2.20). In some cases, NOCs are also tasked with achieving public policy objectives (with Ukraine’s Naftogaz, for example, providing subsidised energy to households).31

Source: Enterprise Surveys and authors’ calculations.

Note: The Enterprise Surveys do not cover firms that are 100 per cent state-owned. In this chart, “state-owned” is defined as a firm where the state owns more than 50 per cent. Asterisks denote differences that are significant at the 5 per cent level in logit models controlling for the logarithm of firm age, the logarithm of employment, city size, sector and country fixed effects, and whether the firm has a board or a business strategy. These estimates are derived from unweighted regressions, with similar results being obtained when using median eligibility sampling weights.

Source: EBRD (2020).

Source: EBRD (2020), ILO, IMF Energy Subsidies Template, national authorities and authors’ calculations.

Note: “Direct employment” refers to employees working at power plants and mines, as well as on-site contractors. “Indirect employment” includes off-site contractors, suppliers and their workers, and jobs created through the distribution of mining products (such as transport and accommodation for mine workers). These estimates do not include induced employment resulting from consumption by direct and indirect employees. Implicit subsidies exceed direct fiscal support and comprise both consumption and production-related subsidies (including damage to public health and the environment that is not reflected in the price of coal).

Source: ILO, National Oil Company Database and authors’ calculations.

Note: Employment data for Azerbaijan and Mexico relate to 2016 and 2017 respectively.

Source: National Oil Company Database and authors’ calculations.

Improving state enterprises’ governance

As previous sections have shown, governments often struggle to manage state enterprises effectively. While market competition and exposure to capital markets have triggered improvements in some cases, poorly run state enterprises still have the potential to pose significant risks to government budgets, divert labour and capital resources away from more efficient uses, and become conduits for corruption. Improvements in governance are key to ensuring that state enterprises are able to deliver value to their ultimate beneficiaries – the taxpayers.

Unique governance challenges

State enterprises face unique governance challenges as a result of the array of financial and non financial objectives that states seek to achieve through their operations – a situation that is further compounded by the complexity of states’ administrative structures. As a shareholder, the state aims to run its enterprises in the interests of society as a whole. In so doing, it should act as an “informed and active owner”, setting high-level objectives and giving state enterprises a clear framework to operate within, while also giving enterprises sufficient autonomy to draw up their own business strategies and pursue those objectives in their preferred manner.36

State ownership policies remain uncommon

The OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises encourage countries to draw up state ownership policies that set out, among other things, the rationale for state ownership and the state’s overall objectives as an owner. In general, however, the objectives of state ownership are not clearly defined in the economies of the EBRD regions (see Chart 2.21), with the state’s ownership often simply a legacy of central planning. Less than a third of all economies in the EBRD regions have formal documents, policies or laws specifying the overarching objectives of state ownership, very few of which qualify as a state ownership policy as such (see also Box 2.6, which looks at the development of a state ownership policy in Uzbekistan).

Lack of transparency around public service obligations

The OECD guidelines also call for public service obligations to be clearly mandated and disclosed. Costs relating to their performance should be funded by the state and subject to high levels of transparency in terms of cost and revenue structures. Such public service obligations are very common, being observed in around 90 per cent of the economies in the EBRD regions. They typically involve providing a universal service (such as postal or railway services) for less than the total cost of delivering it, providing services to specific categories of client at artificially low prices (for instance, supplying electricity or gas to households on the basis of regulated tariffs), or providing subsidised services in specific regions (such as transport services in remote areas). It is typically the case, however, that public service obligations are not clearly defined in regulations and are not explicitly budgeted for. This is true (with exceptions relating to specific enterprises, sectors and services) of almost two-thirds of the economies in the EBRD regions. At firm level, more than 85 per cent of state enterprises do not explicitly disclose the existence of public service obligations or associated budgeting.

Strengthening the disclosure of information

In more than a quarter of all economies in the EBRD regions, information on the loans, grants, subsidies and guarantees that are received by state enterprises is not publicly disclosed in any way. Even in situations where disclosure is legally required, disclosed information is often limited and difficult to access. Corporate governance disclosures are only very limited in 63 per cent of state enterprises in the EBRD regions, and are especially limited in municipally owned companies. Many state enterprises (especially fully state-owned or unlisted enterprises) have no clear audience for this information, so disclosure needs to be a legal requirement. Box 2.7 looks at the successful introduction of a public disclosure system in South Korea, where public institutions are obliged to disclose a range of financial and non-financial information on a regular basis.

Multiple agencies representing the state as owner

In general, the state keeps a firm grip on state enterprises, frequently doing so with multiple hands. The centralised state ownership function that is recommended by the OECD as a best practice – whereby all or most state enterprises are overseen by a single entity – exists in only a quarter of all economies in the EBRD regions. A centralised ownership function can contribute to the streamlining of oversight efforts in the event of multiple state enterprises and can help to draw a clear distinction between the state’s ownership of the enterprise in question and its policymaking and regulatory functions.

Separating ownership and regulatory duties

Conflicts of interest are widespread. The ownership function needs to be adequately separated from the state’s regulatory and policymaking functions in order to ensure a level playing field and avoid undue interference in the operations of state enterprises. However, in almost 45 per cent of economies in the EBRD regions, entities exercising ownership duties are also responsible for deciding on industrial and regulatory policy. Meanwhile, in 19 per cent of countries there are state enterprises that have their own regulatory powers (in the electricity and gas sectors, for instance).

Strengthening the role of state enterprises’ boards

Less than half of the economies in the EBRD regions confer extensive responsibilities on the boards of state enterprises. Strikingly, almost 50 per cent of all state-owned enterprises in the EBRD regions have boards that do not have the authority to approve their enterprises’ strategies or budgets. Boards often lack independence, and it is frequently the case that the composition of boards is not adequate to ensure effective and independent supervision of state enterprises. Moreover, approximately 30 per cent of the economies in the EBRD regions allow high-level and elected officials to sit on the boards of their state enterprises, in contravention of OECD guidelines. It is often the case, too, that the process of appointing people to the board is inconsistent and lacks transparency, with only 15 per cent of the economies in the EBRD regions having a requirement for a nomination policy. While 64 per cent of economies require boards to include independent directors, only 39 per cent have specific requirements relating to the composition of boards which cover all state enterprises, and even these are typically insufficient to ensure balance and diversity of qualifications and backgrounds.

The way forward

The EBRD’s work with clients in the context of corporate governance action plans provides some indication of how state enterprises’ governance can be improved. Clear state ownership policies should be established at country level, while state enterprises need assistance in order to develop strategies that (i) are anchored to their budgets and any public service obligations, (ii) explicitly incorporate potential risks and (iii) can be monitored using measurable key performance indicators (KPIs). Board responsibilities should be strengthened, with boards being granted the authority to carry out strategic planning and oversight, as well as being given control over the use of resources. And the composition of boards should be improved, with greater transparency regarding appointments, disclosure of qualifications and selection processes, and measures to ensure the independence of board members. (Against that background, Box 2.8 looks at how connections affect the effectiveness of both state enterprises and private firms.) Internal control functions should also be improved, with a focus on the reporting of risks to the board.

Source: EBRD and authors’ calculations.

Note: These data are based on a review of the country-level legal frameworks that govern state enterprises in 36 economies in the EBRD regions. The assessment of compliance for the purposes of this chart is loosely based on key recommendations set out in the OECD guidelines, and was prepared after the aggregation of findings across multiple components within each jurisdiction.

Conclusion

State-owned enterprises account for about half of total state employment in the EBRD regions. They dominate the energy and transport sectors, where they are important providers of services such as railway transport and municipal utilities, which are often subsidised to ensure that services are affordable for people living in remote areas and low-income households. While the private sector is able to provide such services under public service obligations with the support of various compensation schemes, countries often rely on the direct provision of services through state enterprises, particularly where their administrative capacity limits their options in terms of the delivery of services.

State enterprises can also act as automatic stabilisers, providing more stable sources of employment during downturns and in disadvantaged regions. For example, the results of a representative household survey conducted by the EBRD and the ifo Institute in August 2020 suggest that employees of state-owned firms were less likely to lose their job or see their income reduced in the early months of the Covid-19 crisis, in line with the developments seen in the aftermath of the 2008-09 global financial crisis. Against that background, public-sector employment tends to play a more important role in regions with higher unemployment rates. More stable employment in the face of adverse economic and technological shocks can help to reduce negative externalities associated with rising inequality and the erosion of social cohesion and trust. Moreover, state enterprises can also play an important role in the winding down of stranded assets in sunset industries such as coal, mitigating the highly localised adverse shocks to employment that result from such developments.

On the other hand, however, governments often struggle to manage state enterprises effectively. For instance, survey evidence suggests that state-owned firms are only half as likely to innovate as equivalent private firms. Moreover, the objectives of state ownership are often not clearly defined in the EBRD regions, and responsibilities relating to state ownership may be spread across multiple state entities with conflicting interests. At the same time, the management of state enterprises is often seen as an exercise in compliance, with little attention being devoted to strategy or risk management. Meanwhile, the fact that the extensive state support provided to such enterprises is not transparent reduces their accountability. And as far as environmental objectives are concerned, there is little evidence that state-run firms are more environmentally friendly than private companies with similar characteristics.

A country’s broader institutional context also matters. Where economic institutions are weak, private firms may become heavily embedded in the networks of state enterprises and politicians, giving rise to rent-seeking behaviour and inefficient allocation of resources. Where economic institutions are strong, however, state companies can be run efficiently while delivering on public service obligations and other non-financial objectives.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the Covid-19 crisis may boost demand for state involvement in the economy and increase support for the expansion of state ownership. This will make it even more important to improve countries’ institutional frameworks and the governance of state enterprises – particularly in terms of setting out the objectives of state ownership, clarifying the ownership responsibilities of state agencies, separating ownership and regulatory functions, and strengthening the independence of state enterprises’ boards.

Box 2.1. State-owned enterprises in the southern and eastern Mediterranean

State-owned enterprises in the southern and eastern Mediterranean region are a legacy of the inward looking socialist policies that were adopted in those economies in the early years following independence. Those enterprises played an important role in the formation of the state, being set up to support industrial and social development in the late 1950s and the 1960s. Firms in the natural resources sector and other strategic sectors were nationalised, with major investment in infrastructure, education and healthcare supporting industrialisation and growth.

Box 2.2. Private-sector involvement in district heating in Romania

In socialist times, district heating was provided as a public service and treated as a natural monopoly for regulatory purposes. That remains the case in many of the economies in the EBRD regions, although some central European countries (such as Poland) have substantially deregulated their district heating sectors. Unlike water or electricity, district heating can potentially face some degree of competition from alternative heat sources (such as individual gas boilers, electric heating or individual stoves fuelled by coal or biomass). Customers can, in theory, opt out of district heating, reducing the revenues of service providers and potentially resulting in inefficient distribution networks.

Box 2.3. Regional distribution of state employment in Poland

This box examines the spatial distribution of state employment in Poland using disaggregated data on employment by type of ownership and sector for 380 Polish powiats (units of local government that are roughly equivalent to UK counties). State employment accounted for about 21 per cent of total employment in Poland in 2018, with that share ranging from about 10 per cent in counties in the regions of Lódzkie (in central Poland) and Mazowieckie (around Warsaw) to 55 per cent in some counties in the coal-mining region of Sląskie.

Source: National Statistics Poland.

Note: “State employment” is defined here as employment by an entity that is more than 50 per cent state-owned.

Box 2.4. Demand for state-led job creation in economically disadvantaged regions

This box looks at people’s views on whether employment creation is primarily the responsibility of the state or the private sector and the ways in which those views vary across regions within individual countries. It is based on the results of the 2018 Euro Survey conducted by the Austrian National Bank, which covered 1,000 randomly selected adults in each of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania and Serbia.45

Box 2.5. ESG objectives of state-owned and private firms: evidence from project proposals submitted to the EBRD

This box analyses the key features of investment proposals submitted to the EBRD in the period 2010-19, with a particular focus on firms’ environmental, social and governance (ESG) objectives. It examines the frequency with which ESG objectives featured in investment proposals, comparing private and public-sector clients,47 with objectives being identified on the basis of textual analysis of economists’ reviews of investment proposals presented to the EBRD’s investment committee.

Data on proposed investment projects

Green energy and energy efficiency are both considered to be environmental objectives. These have been identified on the basis of official statements on the percentage of investment targeting green objectives.48 Social objectives include work aimed at fostering skills and economic inclusion, as well as work on deepening supply chain linkages (typically involving smaller companies). Developing domestic supply chains is a commonly cited objective of industrial policy.49 Large state enterprises, in turn, tend to be important consumers of products and services supplied by other firms or important suppliers of key production inputs. Governance objectives include work on corporate governance and initiatives targeting governance at sector or country level (legislation governing private-public partnerships or tariff reforms, for instance). Social and governance objectives have been identified on the basis of manual coding of a subsample of investment proposals and software-based textual analysis.

State-owned clients are more likely to target corporate governance objectives

First of all, this analysis shows that proposed work with public-sector counterparts is more likely to target corporate governance.50 This difference is statistically significant at the 5 per cent level (see Chart 2.5.1). This is also true of sector and country-level governance, as private-sector clients and their owners have more limited scope to engage with sector-level issues. It is worth noting, however, that these findings on governance related objectives are based only on domestic state-owned companies, not those with cross-border state ownership.

Mixed evidence on environmental and social objectives

Second, state enterprises are significantly less likely to explore issues relating to linkages with their suppliers and off-takers. Projects with those kinds of objective typically seek to train small and medium-sized suppliers, work on quality assurance and standards, or broaden supply chains using smaller local companies. Intuitively, the largest differences between state and private enterprises in this regard can be observed in the industrial and service sectors, and they can be observed for both companies with domestic state ownership and those owned by foreign states. There are no significant differences between state and private enterprises when it comes to issues relating to skills and inclusion (for instance, training programmes, human resources policies or inclusive procurement).

Source: EBRD and authors’ calculations.

Note: Based on 2,935 project proposals considered by the EBRD in the period 2010-19. All regressions are estimated using ordinary least squares and control for the country, the sector and various project-level characteristics. The 90 per cent confidence intervals shown are based on robust standard errors.

Box 2.6. Developing a state ownership policy in Uzbekistan

State-owned enterprises play an important role in the Uzbek economy, with 100 per cent state-owned firms accounting for 19 per cent of GDP. At the same time, establishing effective governance structures and privatising state firms are seen as key objectives in Uzbekistan’s economic reform programme. A new strategy drawn up by the country’s State Assets Management Agency – a government body with a mandate to manage state-owned assets and execute privatisations – sets out the main principles governing the management of state assets, in line with the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises, and is expected to become law.

Box 2.7. Increasing transparency at state enterprises: the experience of South Korea

In 2005, the South Korean government established a public disclosure system – subsequently branded ALIO (All Public Information In-One) – whereby public institutions are obliged to disclose a range of financial and non-financial information on a quarterly or annual basis. By 2019, the initiative had been expanded to cover a total of 339 public corporations, quasi-governmental institutions and other public institutions, with those organisations having a combined budget of around 34 per cent of GDP and accounting for around 1.5 per cent of the country’s total employment. Disclosed data for the last five years are available online at www.alio.go.kr.

Source: Ministry of the Economy and Finance (2020).

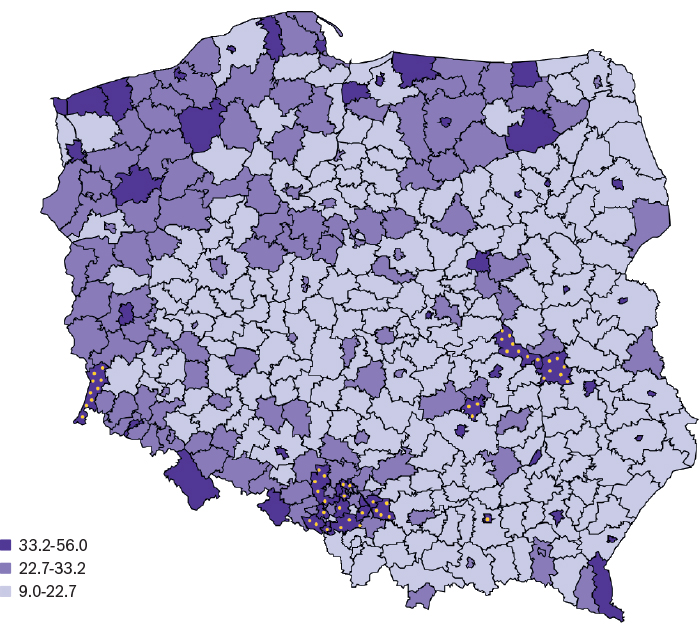

Box 2.8. Well-connected firms

When governments adopt explicit industrial policies, state-owned enterprises often play a major role, especially when those policies target particular sectors or areas of activity. However, in many emerging economies, public policy – including industrial policies – may proceed more stealthily, being shaped by connections between private businesses and the political sphere. Chosen firms thrive by virtue of their close links to power, politicians or political parties. Such links secure privileges for them, whether in terms of finance, assets or resources, or market power. Moreover, a nexus of private companies closely connected to power may work in tandem with large and politicised state-owned enterprises to extract benefits and contracts, including in ways that are tendentiously touted as furthering public interests. Consequently, a simple distinction between private and state firms can be misleading.

Source: Bussolo et al. (2018), using PEPData.

References

AfDB, ADB, EBRD and IDB (2019)

Creating Livable Cities: Regional Perspectives.

A. Alesina, S. Danninger and M. Rostagno (2001)

“Redistribution through public employment: The case of Italy”, IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 48, No. 3, pp. 447-473.

M.-M. Barnes (2019)

“State-owned entities as key actors in the promotion and implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Examples of good practices”, Laws, Vol. 8, No. 2.

S.O. Becker, S. Heblich and D.M. Sturm (2018)

“The impact of public employment: Evidence from Bonn”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 11255.

BEREC (2017)

“Analysis of individual NRAs’ role around access conditions to State aid funded infrastructure”, BoR (17) 246, Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications.

H. Bergsager and A. Korppoo (2013)

“China’s state-owned enterprises as climate policy actors: The power and steel sectors”, TemaNord Paper No. 2013:527.

C.A. Boeing-Reicher and V. Caponi (2016)

“Public wages, public employment, and business cycle volatility: Evidence from U.S. metro areas”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 9965.

S. Borkovic and P. Tabak (2020)

“Economic performance of state-owned enterprises in emerging economies: A cross-country study”, EBRD, London.

B. Bortolotti, V. Fotak and B. Wolfe (2019)

“Innovation at state-owned enterprises”, BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper No. 2018-72.

S. Bradley (2020)

“Transparency in transition: Climate change, energy transition and the EITI”, Energy, Environment and Resources Programme research paper.

S. Bradley, G. Lahn and S. Pye (2018)

“Carbon risk and resilience: How energy transition is changing the prospects for developing countries with fossil fuels”, Energy, Environment and Resources Department research paper.

M. Bussolo, S. Commander and S. Poupakis (2018)

“Political connections and firms: network dimensions”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 11498.

R. Chen, S. El Ghoul, O. Guedhami and H. Wang (2017)

“Do state and foreign ownership affect investment efficiency? Evidence from privatizations”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 42, pp. 408-421.

A. Clark and F. Postel-Vinay (2009)

“Job security and job protection”, Oxford Economic Papers, Vol. 61, pp. 207-239.

S. Commander and S. Poupakis (2020)

“Political networks across the globe”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 13103.

CPI (2014)

“Moving to a low-carbon economy: The impact of policy pathways on fossil fuel asset values”, CPI Energy Transition Series.

EBRD (2018a)

Transition Report 2018-19 – Work in Transition, London.

EBRD (2018b)

Implementing the EBRD green economy transition, London.

EBRD (2019)

Transition Report 2019-20 – Better Governance, Better Economies, London.

EBRD (2020)

“Coal in the EBRD regions: Background paper for the EBRD just transition initiative”, working paper, forthcoming.

M. Eller and T. Scheiber (2020)

“A CESEE conundrum: low trust in government but high hopes for government-led job creation”, Focus on European Economic Integration, Q3/20, Austrian National Bank, Vienna.

S. Estrin, J. Hanousek, E. Kocenda and J. Svejnar (2009)

“The effects of privatization and ownership in transition economies”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 699-728.

S. Estrin, Z. Liang, D. Shapiro and M. Carney (2020)

“State capitalism, economic systems and the performance of state-owned firms”, forthcoming.

S. Estrin and A. Pelletier (2018)

“Privatization in developing countries: What are the lessons of recent experience?”, The World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 33, pp. 65-102.

European Commission (2018)

“Public assets: What’s at stake? An analysis of public assets and their management in the European Union”, Discussion Paper No. 089.

G. Faggio (2014)

“Relocation of public sector workers: Evaluating a place-based policy”, SERC Discussion Paper No. 155.

G. Faggio and H. Overman (2014)

“The effect of public sector employment on local labour markets”, Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 79, pp. 91-107.

V. Foster and A. Rana (2019)

“Rethinking power sector reform in the developing world”, Sustainable Infrastructure Series, World Bank, Washington, DC.

T. Gamtkitsulashvili, G. Jain, A. Plekhanov and A. Stepanov (2020)

“Killing two birds with one stone: Sound investment with social impact”, presented at the Frontiers of Development Economics conference, Korea Development Institute.

P.R.P. Heller and D. Mihalyi (2019)

“Massive and misunderstood: Data-driven insights into national oil companies”, Natural Resource Governance Institute, New York.

P.-H. Hsu, H. Liang and P.P. Matos (2017)

“Leviathan Inc. and corporate environmental engagement”, Research Collection of Lee Kong Chian School of Business.

IDB (2019)

Fixing State-Owned Enterprises: New Policy Solutions to Old Problems, Washington, DC.

IEA (2016)

Energy, Climate Change and Environment: 2016 Insights, Paris.

IEA (2019)

World Energy Outlook 2019, Paris.

IEA (2020)

World Energy Investment 2020, Paris.

IMF (2017)

Republic of Serbia: 2017 Article IV Consultation, Seventh Review under the Stand-By Arrangement and Modification of Performance Criteria, Washington, DC.

IMF (2019)

“Reassessing the Role of State-Owned Enterprises in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe”, European Department, Departmental Paper Series, No. 19/11, Washington, DC.

Institute for Government (2020)

“Location of the civil service”, London: www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/location-of-civil-service (last accessed on 1 September 2020)

P. Jaslowitzer, W. Megginson and M.S. Rapp (2016)

“Disentangling the effects of state ownership on investment – Evidence from Europe”.

S. Kishimoto, L. Steinfort and O. Petitjean (2019)

“The future is public: Towards democratic ownership of public services”, draft prepared for The Future is Public conference.

K. Kou and H. Kroll (2018)

“Innovation output and state ownership: Empirical evidence from China’s listed firms”, Fraunhofer ISI Discussion Paper No. 55.

C. Laabsch and H. Sanner (2012)

“The impact of vertical separation on the success of the railways”, Intereconomics, Vol. 47, No. 2, pp. 120-128.

D. Manley, D. Mihalyi and P.R.P. Heller (2019)

“Hidden Giants”, Finance & Development, Vol. 56, No. 4, IMF, Washington, DC.

P. Matuszak and K. Szarzec (2019)

“The scale and financial performance of state-owned enterprises in the CEE region”, Acta Oeconomica, Vol. 69, pp. 549-570.

M. Mazzucato (2013)

The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths, New York.

W. Megginson (2000)

“Corporate governance in publicly quoted companies”, OECD, Paris.

W. Megginson (2016)

“Privatization, state capitalism, and state ownership of business in the 21st century”, Foundations and Trends in Finance, Vol. 11, No. 1-2.

Ministry of the Economy and Finance (2020)

“Satisfaction with public institutions”, Sejong City: http://kab.co.kr/kab/home/open/cmt_prin.jsp (last accessed on 1 September 2020)

F. Mizutani (2019)

“The impact of structural reforms and regulations on the demand side in the railway industry”, Review of Network Economics, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 1-33.

H. Morsy, B. Kamar and R. Selim (2018)

“Tunisia Diagnostic paper: Assessing Progress and Challenges in Unlocking the Private Sector’s Potential and Developing a Sustainable Market Economy”, EBRD country diagnostic.

H. Mühlenkamp (2013)

“From state to market revisited: More empirical evidence on the efficiency of public (and privately owned) enterprises”, FOV Discussion Paper No. 75.

Natural Resource Governance Institute (2019)

The National Oil Company Database, New York.

OECD (2005)

OECD comparative report on corporate governance of state-owned enterprises, Paris.

OECD (2013)

State-owned enterprises in the Middle East and North Africa: Engines of development and competitiveness?, Paris.

OECD (2015)

State-owned enterprise governance: A stocktaking of government rationales for enterprise ownership, Paris.

OECD (2018a)

Ownership and governance of state-owned enterprises: A compendium of national practices, Paris.

OECD (2018b)

State ownership in the Middle East and North Africa, Paris.

Office of Rail and Road (2019)

Rail Finance: 2018-19 Annual Statistical Release, London.

C.M. O’Toole, E. Morgenroth and T.T. Ha (2016)

“Investment efficiency, state-owned enterprises and privatisation: Evidence from Viet Nam in transition”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 37,

pp. 93-108.

X. Pan, X. Chen, P. Sinha and N. Dong (2020)

“Are firms with state ownership greener? An institutional complexity view”, Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 29, pp. 197-211.

A. Prag, D. Röttgers and I. Scherrer (2018)

“State-owned enterprises and the low-carbon transition”, OECD Environment Working Paper No. 129.

D. Rodrik (2005)

“Growth Strategies”, in P. Aghion and S. Durlauf (eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth, Vol. 1, pp. 967-1014.

Salience Consulting (2020)

“Privatisation experience of state-owned telecom incumbents in the world and lessons for the EBRD region”.

T. Schluter (2014)

“The spatial dimension of labour markets: An investigation of economic inequalities and a local employment shock”, PhD thesis, London School of Economics.

J.-C. Spinetta (2018)

“L’avenir du transport ferroviaire”, report submitted to the French Prime Minister.

P. Swinney and G. Piazza (2017)

“Should we move public sector jobs out of London?”, Centre for Cities briefing.

K. Szarzec, A. Dombi and P. Matuszak (2019)

“State-owned enterprises and economic growth: Evidence from the post-Lehman period”.

A. Telegdy (2016)

“Employment adjustment in the global crisis: Differences between domestic, foreign and state-owned enterprises”, Economics of Transition and Institutional Change, Vol. 24, pp. 683-703.

Z. Tomeš (2017)

“Do European Reforms Increase Modal Shares of Railways?”, Transport Policy, Vol. 60, pp. 143-151.

UNCTAD (2017)

World Investment Report 2017, Geneva.

D. Van de Velde, C. Nash, A. Smith, F. Mizutani, S. Uranishi, M. Lijesen and F. Zschoche (2012)

“EVES-Rail: Economic Effects of Vertical Separation in the Railway Sector”, Community of European Railways and Infrastructure Companies.

M. Vladisavljević (2020)

“Wage premium in the state sector and state‐owned enterprises: Econometric evidence from a transition country in times of austerity”, Economics of Transition and Institutional Change, Vol. 28, pp. 345-378.

Working Party on Rail Transport (2012)

“Railway Reform”, Informal Document SC.2, No. 3. Available at: www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/doc/2012/sc2/ECE-TRANS-SC2-2012-infdoc03e.pdf (last accessed on 1 September 2020)

World Bank (2006)

Held by the visible hand: The challenge of SOE corporate governance for emerging markets, Washington, DC.

World Bank (2011)

National Oil Companies and Value Creation, Washington, DC.

World Bank (2015)

“Middle East and North Africa: Governance Reforms of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)”, Report No. ACS15142, Washington, DC.

World Bank (2017)

Railway reform: A toolkit for improving rail sector performance, Washington, DC