Structural reform

This section of the report presents updated transition scores for the economies in the EBRD regions and discusses the reforms that have been carried out in those economies over the last year. Successfully implementing structural reforms is not an easy task at the best of times, and it is even more difficult in times of crisis, when policymakers’ focus shifts from addressing longer-term issues to tackling immediate challenges. In the EBRD regions, the ongoing coronavirus pandemic has probably affected governments’ ability to implement further structural reforms in the short term. At the same time, however, the economic and social fallout from the pandemic has emphasised the need for continued structural reform measures across the EBRD regions in order to ensure that economies recover quickly and become more resilient to external shocks.

Introduction

Governments across the EBRD regions have implemented a wide range of measures in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Those actions, which have been unprecedented in terms of their scope and the speed of their implementation, have ranged from the provision of liquidity to the banking system and moratoriums on loan repayment to various tax breaks for businesses and direct payments for households. With policymakers having so many urgent health and economic issues to deal with, the likelihood of structural reforms being postponed – or abandoned altogether – has increased. However, while it might well be more difficult to implement structural reforms during a crisis (see Box S.1), carrying out essential reforms has the potential to facilitate a stronger economic recovery and make the economy more resilient to future shocks.

Source: EBRD.

Note: Scores range from 1 to 10, where 10 denotes the synthetic frontier for each quality.

| Competitive | Well-governed | Green | Inclusive | Resilient | Integrated | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2019 | 2016 | 2020 | 2019 | 2016 | 2020 | 2019 | 2016 | 2020 | 2019 | 2016 | 2020 | 2019 | 2016 | 2020 | 2019 | 2016 | |

| Central Europe and the Baltic states | ||||||||||||||||||

| Croatia | 5.91 | 5.85 | 5.84 | 6.10 | 6.04 | 6.21 | 6.27 | 6.40 | 6.18 | 6.41 | 6.36 | 6.49 | 7.60 | 7.49 | 7.27 | 6.67 | 6.59 | 6.68 |

| Estonia | 7.48 | 7.45 | 7.42 | 8.38 | 8.39 | 8.41 | 6.45 | 6.45 | 6.68 | 7.61 | 7.58 | 7.58 | 8.03 | 7.94 | 7.86 | 7.57 | 7.57 | 7.63 |

| Hungary | 6.64 | 6.58 | 6.48 | 5.98 | 5.96 | 5.69 | 6.14 | 6.27 | 6.39 | 6.53 | 6.54 | 6.69 | 7.06 | 7.14 | 6.76 | 7.08 | 7.18 | 7.73 |

| Latvia | 6.58 | 6.49 | 6.45 | 7.00 | 6.95 | 6.77 | 6.74 | 6.87 | 6.51 | 7.07 | 6.99 | 7.16 | 7.53 | 7.50 | 7.39 | 7.08 | 7.16 | 7.53 |

| Lithuania | 6.49 | 6.38 | 6.48 | 7.41 | 7.17 | 7.21 | 6.63 | 6.75 | 6.45 | 6.91 | 6.83 | 6.83 | 7.53 | 7.37 | 7.46 | 7.23 | 7.20 | 7.35 |

| Poland | 6.78 | 6.81 | 6.67 | 6.86 | 7.00 | 7.28 | 6.51 | 6.51 | 6.65 | 6.93 | 6.89 | 6.65 | 7.74 | 7.71 | 7.92 | 7.11 | 7.01 | 6.93 |

| Slovak Republic | 6.67 | 6.61 | 6.59 | 6.31 | 6.34 | 6.14 | 6.74 | 6.87 | 7.02 | 6.51 | 6.50 | 6.39 | 7.90 | 7.92 | 7.80 | 7.32 | 7.31 | 7.56 |

| Slovenia | 6.96 | 6.91 | 6.84 | 7.20 | 7.09 | 7.08 | 6.97 | 7.11 | 6.81 | 7.43 | 7.42 | 7.32 | 7.73 | 7.69 | 7.72 | 7.28 | 7.38 | 7.32 |

| South-eastern Europe | ||||||||||||||||||

| Albania | 5.25 | 5.18 | 4.88 | 4.50 | 5.16 | 5.09 | 4.43 | 4.43 | 4.50 | 5.25 | 5.26 | 5.31 | 5.65 | 5.44 | 5.15 | 5.76 | 5.85 | 5.57 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 4.80 | 4.72 | 4.88 | 3.98 | 4.12 | 4.49 | 5.14 | 5.15 | 4.95 | 5.43 | 5.41 | 5.21 | 6.09 | 6.08 | 5.84 | 5.41 | 5.35 | 5.19 |

| Bulgaria | 5.90 | 5.82 | 5.72 | 6.19 | 5.97 | 5.84 | 5.93 | 6.06 | 5.85 | 6.32 | 6.27 | 6.19 | 6.89 | 6.82 | 6.81 | 7.01 | 7.02 | 7.06 |

| Cyprus | 6.94 | 6.90 | 6.85 | 7.30 | 7.34 | 6.84 | 6.24 | 6.36 | 6.07 | 6.69 | 6.65 | 6.62 | 5.82 | 5.71 | 5.09 | 7.85 | 7.82 | 7.60 |

| Greece | 5.94 | 5.90 | 5.95 | 5.82 | 5.64 | 5.54 | 6.03 | 6.16 | 6.18 | 6.28 | 6.19 | 6.13 | 7.19 | 7.04 | 6.85 | 6.61 | 6.59 | 6.16 |

| Kosovo | 5.21 | 5.13 | 4.49 | 4.61 | 4.75 | 4.74 | 3.41 | 3.41 | 3.41 | 5.34 | 5.33 | 5.33 | 5.41 | 5.21 | 5.09 | 5.10 | 4.97 | 4.74 |

| Montenegro | 5.60 | 5.56 | 5.28 | 6.27 | 6.11 | 5.86 | 5.44 | 5.45 | 5.08 | 6.07 | 6.06 | 5.99 | 6.83 | 6.45 | 6.33 | 6.29 | 6.18 | 5.84 |

| North Macedonia | 5.98 | 5.94 | 5.74 | 5.40 | 5.43 | 5.71 | 5.27 | 5.27 | 5.03 | 5.76 | 5.74 | 5.75 | 6.21 | 5.96 | 5.63 | 6.13 | 6.07 | 5.80 |

| Romania | 6.32 | 6.29 | 6.19 | 6.10 | 6.17 | 5.89 | 5.99 | 6.13 | 5.88 | 5.70 | 5.71 | 5.64 | 7.17 | 7.19 | 7.20 | 7.01 | 7.00 | 6.88 |

| Serbia | 5.64 | 5.54 | 5.30 | 5.84 | 5.77 | 5.66 | 5.78 | 5.79 | 5.55 | 6.13 | 6.06 | 6.33 | 5.94 | 5.85 | 5.74 | 6.25 | 6.24 | 6.26 |

| Turkey | 5.71 | 5.51 | 5.53 | 5.92 | 6.08 | 6.01 | 5.24 | 5.25 | 5.32 | 4.99 | 4.95 | 4.94 | 7.09 | 7.04 | 7.13 | 5.98 | 5.87 | 6.00 |

| Eastern Europe and the Caucasus | ||||||||||||||||||

| Armenia | 4.84 | 4.76 | 4.49 | 6.13 | 5.80 | 5.68 | 5.76 | 5.75 | 5.51 | 5.89 | 5.94 | 5.78 | 6.63 | 6.52 | 6.22 | 5.91 | 5.80 | 5.45 |

| Azerbaijan | 4.54 | 4.30 | 4.14 | 5.58 | 5.31 | 5.04 | 5.37 | 5.37 | 5.14 | 5.07 | 4.93 | 4.73 | 4.09 | 4.00 | 4.11 | 5.95 | 5.85 | 5.61 |

| Belarus | 5.11 | 5.04 | 4.56 | 5.01 | 4.86 | 4.63 | 6.24 | 6.24 | 6.20 | 6.68 | 6.68 | 6.69 | 4.32 | 4.36 | 3.62 | 5.97 | 5.94 | 5.59 |

| Georgia | 5.21 | 5.15 | 4.73 | 6.42 | 6.45 | 6.46 | 5.38 | 5.37 | 5.16 | 5.20 | 5.17 | 5.08 | 6.16 | 6.19 | 5.84 | 6.49 | 6.48 | 6.17 |

| Moldova | 4.67 | 4.58 | 4.64 | 4.84 | 4.92 | 4.49 | 4.36 | 4.36 | 4.21 | 5.61 | 5.51 | 5.68 | 5.90 | 5.87 | 5.30 | 5.21 | 5.21 | 5.18 |

| Ukraine | 5.10 | 5.03 | 4.99 | 4.18 | 4.39 | 4.08 | 6.01 | 6.01 | 5.75 | 6.14 | 6.17 | 6.20 | 6.14 | 5.80 | 4.92 | 5.19 | 4.99 | 4.98 |

| Russia | 6.16 | 6.11 | 5.57 | 5.66 | 5.65 | 5.35 | 5.35 | 5.10 | 5.10 | 6.97 | 6.96 | 6.74 | 6.45 | 6.40 | 6.44 | 5.02 | 5.06 | 5.00 |

| Central Asia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kazakhstan | 5.35 | 5.26 | 5.14 | 5.81 | 5.64 | 5.53 | 5.34 | 5.34 | 4.85 | 6.42 | 6.38 | 6.37 | 6.14 | 6.04 | 6.06 | 5.04 | 4.99 | 5.00 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 4.19 | 4.00 | 3.85 | 4.08 | 4.05 | 3.99 | 4.45 | 4.44 | 4.50 | 4.67 | 4.56 | 4.83 | 5.20 | 5.19 | 5.14 | 4.64 | 4.67 | 4.56 |

| Mongolia | 4.24 | 4.20 | 4.09 | 4.94 | 5.07 | 5.28 | 5.42 | 5.41 | 5.39 | 5.25 | 5.12 | 5.39 | 5.36 | 5.40 | 5.26 | 4.66 | 4.76 | 5.13 |

| Tajikistan | 3.40 | 3.23 | 3.16 | 4.17 | 3.81 | 3.85 | 4.78 | 4.78 | 4.58 | 5.13 | 5.02 | 4.67 | 4.16 | 3.89 | 3.43 | 3.99 | 3.72 | 3.42 |

| Turkmenistan | 2.87 | 2.73 | 2.80 | 2.48 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 4.23 | 4.23 | 4.10 | 5.39 | 5.49 | 5.29 | 3.51 | 3.29 | 3.41 | 4.11 | 4.08 | 4.22 |

| Uzbekistan | 3.48 | 3.42 | 3.36 | 3.84 | 3.81 | 3.76 | 4.80 | 4.79 | 3.93 | 5.51 | 5.50 | 5.60 | 4.58 | 3.98 | 3.84 | 4.18 | 4.06 | 4.06 |

| Southern and eastern Mediterranean | ||||||||||||||||||

| Egypt | 3.38 | 3.18 | 3.35 | 4.95 | 4.71 | 4.42 | 5.11 | 5.10 | 4.78 | 3.54 | 3.56 | 3.62 | 5.62 | 5.31 | 5.12 | 4.85 | 4.78 | 4.43 |

| Jordan | 4.45 | 4.15 | 4.11 | 5.72 | 5.62 | 5.65 | 5.66 | 5.78 | 5.84 | 4.49 | 4.39 | 4.49 | 6.01 | 6.04 | 5.74 | 5.67 | 5.66 | 5.92 |

| Lebanon | 4.44 | 4.43 | 4.43 | 3.92 | 3.96 | 3.97 | 5.07 | 5.08 | 5.09 | 4.71 | 4.71 | 4.86 | 4.17 | 4.51 | 4.20 | 4.80 | 4.82 | 4.94 |

| Morocco | 4.45 | 4.17 | 4.09 | 5.76 | 5.58 | 5.33 | 5.87 | 5.86 | 5.90 | 3.33 | 3.18 | 3.45 | 5.85 | 5.82 | 5.84 | 5.02 | 5.07 | 5.07 |

| Tunisia | 4.15 | 4.02 | 4.13 | 4.90 | 4.96 | 4.95 | 4.88 | 4.88 | 4.68 | 3.94 | 3.85 | 4.06 | 5.17 | 5.09 | 4.76 | 4.64 | 4.58 | 4.38 |

| West Bank and Gaza | 2.75 | 2.67 | 2.44 | 3.76 | 3.64 | 3.60 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.02 | 3.82 | 3.88 | 4.00 | 4.91 | 4.98 | 4.80 | 4.70 | 4.60 | 4.54 |

SOURCE: EBRD.

NOTE: Scores range from 1 to 10, where 10 represents a synthetic frontier corresponding to the standards of a sustainable market economy. Scores for years prior to 2020 have been updated following methodological changes, so they may differ from those published in the Transition Report 2019-20. Owing to lags in the availability of underlying data, ATQ scores for 2020 and 2019 may not fully correspond to that calendar year.

Competitive

ATQ scores for competitiveness have increased modestly over the last year, being driven primarily by gradual improvements in indicators measuring the ease of doing business. The largest increases have been observed in the southern and eastern Mediterranean (Egypt, Jordan and Morocco) and Central Asia (the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan), driven by improvements in the ease of doing business and the quality of workers’ skills. Turkey and Azerbaijan have also seen their scores rise, with increases in those countries being driven by declines in the cost of starting a business and improvements to their arrangements for resolving insolvencies. No significant declines have been observed over the last year.

Well-governed

Effective governance will be crucial in order to deliver a green, resilient and inclusive recovery across the EBRD regions. The various subcomponents of the governance index suggest that governments in those regions still need to do more to improve communication with their citizens, make public spending more transparent and strengthen their capacity for sound policymaking. At the same time, the crisis has placed greater emphasis on governments’ ability to make sound policy decisions, mobilise the necessary resources and coordinate actions across multiple stakeholders (both at domestic level and internationally).

Green

Green scores have not generally seen significant changes over the last year – with the sole exception of Russia, where a notable increase has been observed as a result of the ratification of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change in September 2019. In several countries, however, downward revisions have been made to scores measuring the effectiveness of carbon-pricing mechanisms, with declines being recorded for Croatia, Jordan, Latvia, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia as a result of a recommended carbon price of US$ 40 being used as a benchmark in 2020 (up from US$ 10 previously).1

Inclusive

Overall, ATQ scores for inclusion have increased modestly over the last year across a number of economies. Notable increases have been seen in Mongolia and Morocco (on account of increases in the proportion of total employers that are women) and Azerbaijan (following improvements to the flexibility of hiring and firing for young people).

Resilient

Energy

ATQ scores for energy resilience have remained unchanged in most economies over the last year, with the exception of increases in Montenegro, Tajikistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan (as a result of improvements in regulation and progress with the restructuring of the power sector).

Those developments appear to be consistent with longer-term trends observed over the period 2016-20. For instance, scores for Ukraine and Uzbekistan have increased considerably over that period on account of continued efforts to improve the regulations governing the power sector. In particular, following a multi-year process supported by international financial institutions (including the EBRD), the Ukrainian state-owned gas company Naftogaz was unbundled in 2019 in line with the EU’s Third Energy Package and a new gas transport company was created. It is expected that the unbundling of the main incumbent in the Ukrainian gas sector will pave the way for further liberalisation of the country’s gas market.

Financial institutions

On balance, increases in financial resilience scores have outnumbered declines over the last year. The largest increases have been observed in Egypt, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Ukraine and Uzbekistan, driven by improved capital adequacy ratios, improvements to the funding structure of the banking sector, and advances in respect of risk management and corporate governance frameworks. However, Lebanon’s financial resilience score has declined on account of significant vulnerabilities observed in its financial sector.

Integrated

A few economies (including Kosovo, Tajikistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan) have seen their ATQ scores for integration improve over the last year, mainly reflecting reductions in the cost of cross-border trading.

Integration scores have improved for many economies over the period 2016-20, with significant increases being observed in Armenia, Egypt, Greece, Montenegro and Tajikistan on account of continued improvements in the performance of logistics, greater inflows of capital other than foreign direct investment (FDI), improved conditions for attracting FDI and greater financial openness. At the same time, scores have declined significantly in Hungary, Latvia and Mongolia over that period as a result of a sustained drop in FDI inflows as a percentage of GDP (Hungary and Mongolia) and a deterioration in the performance of logistics (Latvia).

Box S.1. Implementing reforms in times of crisis

The Covid-19 crisis has resulted in rising unemployment, a decline in consumer demand and liquidity constraints for both businesses and households. In such circumstances, the government can play a key role by limiting the lasting economic damage caused by the crisis. In these kinds of situation, structural reforms (which are often regarded as yielding benefits primarily in the long term) could potentially be overlooked in favour of short-term stimulus measures. This raises an important question as to whether crises alter the costs and benefits of structural reforms and whether they warrant the postponement or overhaul of such measures. With that question in mind, this box summarises empirical evidence on the implementation of reforms during crises.

Methodological notes

Transition indicators: six qualities of a sustainable market economy

The transition indicators reflect the judgement of the EBRD’s Office of the Chief Economist and the Economics, Policy and Governance department on the transition progress in the economies where the EBRD invests. According to this approach a sustainable market economy is characterised by six qualities: Competitive, Well-governed, Green, Inclusive, Resilient and Integrated.

This approach measures the state of each quality and its components in a given economy, as compared with the other economies in the EBRD regions and a few select developed economies,12 against a frontier. The frontier is set either by the best performance in this group of economies or by an unobserved theoretical value and provides a common benchmark against which all economies are assessed consistently and comparably. The same frontier values are also applied across the years to ensure that computed scores are comparable and capture changes in underlying indicators through time.

Assessments of Transition Qualities (ATQs) are composite indices combining information from a large number of indicators and assessments in a consistent manner. The underlying indicators within each ATQ are constructed using a wide range of sources, including national and industry statistics, data from other international organisations and affiliated databases (World Bank, IMF, UN); surveys (The Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS); Life in Transition Survey (LiTS) and assessments prepared internally by EBRD experts (see Table M.1 below for the list of indicators).

The computation of ATQ indices involves multiple steps, namely: data preparation, normalisation and aggregation. Details of each of these steps are provided below.

Data preparation and treatment of missing observations

The underlying data for the majority of indicators either enter the composite index directly or are scaled using a meaningful related measure. A number of indicators may themselves be composite indices (for example, EBRD SME index or EBRD Knowledge Economy index) and they enter the ATQ composites in index form. No further transformation is applied to the underlying indicators before normalisation. For some indicators no data is available for the current year and simple imputation methods are used.13 One method of imputation uses the latest available observation from past years, thus assuming that no change from the latest available observation has been observed. When there are no past or present observations available for a particular indicator, then, based on the judgement of EBRD experts, either the regional mean (using the EBRD classification of regions for the economies where it invests) or the observed regional minima are used to impute the missing observations.

For the regional disparity component of the Inclusive ATQ, imputations for the southern and eastern Mediterranean (SEMED) economies and Turkmenistan are necessary due to the LiTS (source of the data for this indicator) not being administered in these economies. In particular, a new series is generated for a full set of economies including SEMED and Turkmenistan based on available indicators on rural-urban disparities from other sources. Using the statistical relationship between the scores produced by this series and LiTS-based regional inclusions scores, missing SEMED and Turkmenistan values were imputed. Further details of this imputation are available on request.

To mitigate the effect that extreme values may have on scores, observations that lie above the 98th percentile are considered outliers and replaced by the next value within the acceptable range. Outlier detection and replacement is only applied to select continuous variables.

Normalisation

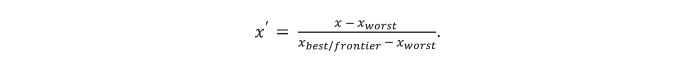

The raw data for each indicator are normalised to the same scale using the min-max normalisation method as follows:

The resulting scores are then rescaled from 1 to 10, where 10 represents the frontier for each quality. The frontier is taken to be the best performance, observed either in an economy where we invest, a comparator country or a theoretical value determined based on expert judgement.

If an observation for a country exceeds the selected frontier, then the normalised value of the indicator is capped at the frontier value. For indicators where any deviation from the frontier is undesirable, values either below or above the frontier are treated similarly (the same score is computed and assigned to two observations that are equally distant from the frontier).

Aggregation

Normalised indicators are aggregated to a single composite index (by quality) using weights determined by expert judgement (see Table M.1 for details of weights). A simple weighted averaging method is used for aggregation.

Changes to methodology from 2019

During the past year, further work on strengthening the methodology for computing ATQ indices was carried out. This work did not involve changes to the process of computation of ATQ indices and it focused largely on modifications to the set of underlying indicators. The primary purpose of this work has been ensuring that ATQs better capture the relevant phenomena and allow adequate monitoring of the pace of reforms and transformation in the region. This work resulted in the addition of new indicators, discontinuation of the use of others and use of equivalent data series from alternative sources. Details of these changes are provided below.

Competitive

- The indicator measuring the quality of the education system was removed. An alternative indicator measuring skills and education of the workforce was added to the composite index.

- An adjusted version of the “Competition Law, Institutions and Enforcement” index produced by the EBRD was added to the composite index.

Well-governed

- The following indicators were added to the composite index: budget transparency, e-government participation, political and operational stability, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism and assessment of governments in ensuring political stability.

- The following indicators were removed from the composite index: transparency of government policymaking, ethical behaviour of firms, one of the indicators measuring freedom of media and one of the indicators measuring perception of corruption.

- The weight of the corporate governance component of the composite index was revised downwards to 25 per cent, from 40 per cent.

Integrated

A new indicator measuring road connectivity produced by the EBRD was added to the composite index. It replaced the previously used indicators on the quality of roads and connectivity.

The following tables show, for each quality, the components used in each quality index along the indicators and data sources that were fed into the final assessments.

| COMPETITIVE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier economy | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| Market structures [53%] | Applied tariff rates a (weighted average) [13%] | World Bank, World Development Indicators (WDI), International Trade Centre, Market Access Map, 2018 | Georgia | 0.67 | 9.35 | |

| Subsidies expense a (share of GDP) [13%] | International Monetary Fund, Government Finance Statistics, 2018 | Albania | 0.13 | 7.05 | ||

| Ease of Doing Business (Distance to frontier (DTF) score) [13%] | World Bank, Doing Business, 2020 | United States of America | 84.99 | 51.84 | ||

| Doing Business – resolving insolvency score [13%] | World Bank, Doing Business, 2020 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 91.07 | 20.30 | ||

| Number of new business entries (scaled by population) [6%] | World Bank, WDI, 2018 | Estonia | 19.43 | 0.15 | ||

| Doing Business – starting a business [6%] | World Bank, Doing Business, 2020 | Canada* | 98.23 | 57.14 | ||

| SME index adjusted (1 = worst, 10 = best) [13%] | EBRD assessment, 2018 | United Kingdom | 7.73 | 3.52 | ||

| Competition Law, Institutions and Enforcement index adjusted (1 = worst, 10 = best) [13%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | United Kingdom | 8.02 | 4.89 | ||

| Share of advance business services in services exports [13%] | World Bank, WDI, 2017 | United Kingdom | 72.08 | 6.60 | ||

| Capacity to generate value added [47%] | Economic Complexity Index [14%] | Harvard, Centre for International Development, 2017 | Japan | 2.34 | -1.52 | |

| Knowledge economy index (KEI) adjusted (1 = worst, 10 = best) [14%] | EBRD, 2019 | Sweden | 8.02 | 1.92 | ||

| WB Logistics Performance Index (1 = worst, 5 = best) [14%] | World Bank, WDI, 2018 | Germany | 4.37 | 1.96 | ||

| Skills [14%] | World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 84.60 | 45.18 | ||

| Labour productivity (output per worker, GDP in constant 2011 int. US$ PPP) [14%] | ILOSTAT, WDI, 2020 | United States of America | 112,007 | 8,496 | ||

| Credit to private sector b (per cent of GDP) [14%] | World Bank, WDI, 2018 | Cyprus* | 100 | 12.33 | ||

| Global value chain participation [14%] | UNCTAD, EBRD, 2018 | Slovak Republic | 0.81 | 0.33 | ||

| WELL-GOVERNED | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier economy | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| National level governance [75%] | Quality of public governance [53%] | Regulatory quality (- 2.5 = worst, 2.5 = best) [13%] | World Bank Governance Indicators, 2018 | Sweden | 1.80 | -2.09 |

| Government effectiveness (- 2.5 = worst, 2.5 = best) [13%] | World Bank Governance Indicators, 2018 | Sweden | 1.83 | -1.21 | ||

| Budget transparency (1 = worst, 7 = best) [6%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 88.46 | 3 | ||

| Private property protection (1 = worst, 7 = best) [6%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | Japan | 6.21 | 2.87 | ||

| Intellectual property protection (1 = worst, 7 = best) [6%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 6.01 | 2.91 | ||

| Burden of government regulation (1 = worst, 7 = best) [13%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | Azerbaijan | 4.83 | 1.85 | ||

| Political instability a [4%] | World Bank/EBRD BEEPS, 2018-20 | Azerbaijan | 0 | 0.96 | ||

| Political stability and absence of violence and terrorism (-2.5 = worst, 2.5 = best) [4%] | World Bank Governance Indicators, 2018 | Japan | 1.06 | -2.01 | ||

| Political and operational stability [4%] | Global Innovation Index, 2019 | Canada* | 93 | 43.90 | ||

| Government ensuring policy stability (1 = worst, 7 = best) [6%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 5.52 | 1.83 | ||

| World press freedom index a (100 = least free, 0 = most free) [13%] | Reporters Without Borders, 2020 | Sweden* | 12.16 | 85.44 | ||

| E-government participation [13%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0.98 | 0.20 | ||

| Integrity and control of corruption [20%] | Corruption perception index (0 = highly corrupt, 100 = not corrupt) [43%] | Transparency International, 2019 | Sweden | 84 | 19 | |

| Perception of corruption a [14%] | World Bank/EBRD BEEPS, 2018-20 | Sweden | 2.70 | 68.20 | ||

| Informality a [14%] | World Bank/EBRD BEEPS, 2018-20 | Azerbaijan | 7.10 | 63.40 | ||

| Implementation of anti-money laundering (AML)/combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) and tax exchange standards a (0 = low risk, 10 = high risk) [29%] | International Centre for Asset Recovery, 2019 | Estonia* | 3.22 | 8.30 | ||

| Rule of law [27%] | Judicial independence (1 = worst, 7 = best) [22%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 6.19 | 1.99 | |

| Efficiency of legal framework in settling disputes (1 = worst, 7 = best) [11%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 5.55 | 1.86 | ||

| Efficiency of legal framework in challenging regulations (1 = worst, 7 = best) [22%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 5.17 | 1.79 | ||

| Enforcement of contracts [11%] | World Bank Doing Business, 2020 | Lithuania* | 78.80 | 40.00 | ||

| Rule of law (- 2.5 = worst, 2.5 = best) [22%] | World Bank Governance Indicators, 2018 | Sweden | 1.90 | -1.49 | ||

| Effectiveness of courts a [11%] | World Bank/EBRD BEEPS, 2018-20 | Montenegro* | 0.60 | 42.80 | ||

| Corporate level governance [25%] | Corporate governance frameworks and practices [100%] | Structure and functioning of the board [20%] | EBRD Legal Transition Team (LTT) Corporate Governance Assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 3.55 | 1.34 |

| Transparency and disclosure [10%] | EBRD LTT Corporate Governance Assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 4.53 | 1.63 | ||

| Internal control [20%] | EBRD LTT Corporate Governance Assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 4.03 | 1.53 | ||

| Rights of shareholders [10%] | EBRD LTT Corporate Governance Assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 4.15 | 2.35 | ||

| Stakeholders and institutions [20%] | EBRD LTT Corporate Governance Assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 4.06 | 0.98 | ||

| Strength of auditing and reporting standards (1 = worst, 7 = best) [10%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 6.03 | 3.33 | ||

| Protection of minority shareholders’ interest [10%] | World Bank Doing Business, 2020 | Georgia* | 84 | 32 | ||

| GREEN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier economy | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| Mitigation [35%] | Physical indicators [37%] | Electricity production from renewable sources, including hydroelectric (per cent of total) [17%] | World Bank, International Energy Agency (IEA), 2017 | Albania | 100 | 1.25 |

| Value added from industry (construction, manufacturing, mining, electricity, water and gas) per unit of CO2 emissions from industry (GVA (US$)/total CO2) [17%] | World Bank, IEA, 2017 | Sweden | 18,680 | 697 | ||

| MWh consumed per tonne of CO2 emitted from electricity and heat generation (MWh/total CO2) [17%] | World Bank, IEA, 2017 | Sweden | 18.79 | 0.50 | ||

| GDP per tonne of CO2 emitted from residential buildings (from fuel combustion) (GDP(US$)/total CO2) [17%] | World Bank, IEA, 2017 | Sweden | 2,649,844 | 7,448 | ||

| Number of registered vehicles per tonne of CO2 emitted from transport [17%] | World Health Organization (WHO), IEA, 2012 | Lebanon | 7.38 | 0.79 | ||

| Agricultural sector GVA per tonne of GHG emissions from agriculture (GVA (US$) / total CO2eq) [17%] | World Bank, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 2,800 | 61 | ||

| Structural indicators [63%] | Market support mechanism for renewable energy production (0=no support, 0.5 regulatory support, 1=revenue support) [25%] | IEA, 2019 | Canada* | 1 | 0.50 | |

| INDC rating (0 for no INDC. 0.5 for INDC but not ratified. 1 for ratified INDC) [25%] | World Resources Institute (WRI), CAIT, 2019 | Canada* | 1 | 0 | ||

| Carbon price (0 = worst, 1 = best) [25%] | World Bank, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Fossil fuel subsidies (per cent of GDP) a [25%] | IMF, 2017 | Sweden* | 0 | 11.91 | ||

| Adaptation [30%] | Physical indicators [45%] | NDGAIN human habitat score a [25%] | Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative, 2017 | Germany | 0.25 | 0.63 |

| Aqueduct water stress index a [25%] | World Resources Institute (WRI), 2013 | Slovenia | 0.83 | 3.14 | ||

| NDGAIN projected change in cereal yield a [25%] | Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative, 2017 | Canada* | 0 | 0.85 | ||

| WDI Occurrence of droughts, floods, extreme temperatures a (per cent of population affected 1990-2009) [25%] | World Bank, WDI, 2009 | Sweden* | 0 | 5.38 | ||

| Structural indicators [55%] | NDGAIN agricultural capacity a [20%] | Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative, 2017 | Turkmenistan | 0 | 0.99 | |

| World Governance Indicators: Institutional Quality ( – 2.5 = worst, 2.5 = best) [40%] | World Bank, World Governance Indicators, 2018 | Sweden | 1.82 | -1.61 | ||

| Adaptation mentioned in INDCs (1 = yes, 0 = no) [40%] | CGSpace, CGIAR, 2019 | Armenia* | 1.00 | 0 | ||

| Other environmental areas [30%] | Physical indicators [37%] | Population weighted mean annual exposure to PM2.5 a [22%] | World Bank, WDI, 2017 | Sweden | 6.18 | 88.15 |

| Waste intensive consumption (kg municipal solid waste/US$ household expenditure) a [22%] | Waste Atlas, 2015 | Japan | 0.01 | 0.33 | ||

| Waste generation per capita (kg/cap) a [22%] | Waste Atlas, 2015 | Armenia | 118.90 | 777 | ||

| Number of animal (terrestrial and marine) species threatened as proportion of total number assessed a [17%] | IUNC Red list, 2019 | Estonia | 0.04 | 0.18 | ||

| Number of plant (terrestrial and marine) species threatened normalised by total number assessed a [17%] | IUNC Red list, 2019 | Mongolia | 0 | 0.27 | ||

| Structural indicators [63%] | Vehicle emission standards (0 = worst, 6 = best) [34%] | UN Environment Programme, 2018 | Germany* | 6 | 0 | |

| Municipal solid waste collected (per cent of total generated) [34%] | Waste Atlas, 2015 | Germany* | 100 | 39 | ||

| Proportion of terrestrial protected area (per cent of total area) [16%] | World Bank, 2017 | Slovenia | 53.62 | 0.22 | ||

| Proportion of marine protected areas (per cent of total area) [16%] | World Bank, 2017 | Slovenia | 213.43 | 0 | ||

| Cross-cutting [5%] | Number of environmental technology patents (per cent of GDP (billion US$)) [100%] | OECD, 2017 | Japan | 0.31 | 0 | |

| INCLUSIVE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier economy | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| Gender equality [33%] | Women Business and the Law Index (0 = worst, 100 = best) [13%] | World Bank, 2020 | Sweden* | 100 | 26.30 | |

| Social Institutions and Gender Index a, b (0 = best) [13%] | OECD, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0 | 0.57 | ||

| Inequality of opportunity attributable to gender a, b [13%] | EBRD, LITS, 2016 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0 | 0.08 | ||

| Women employers (per cent of employers) c [13%] | ILOSTAT, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 50.00 | 0 | ||

| Women in managerial roles (per cent of all in managerial roles) c [13%] | ILOSTAT, 2018 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 50.00 | 6.40 | ||

| Per cent of individuals that borrow from a financial institution [6%] | World Bank Financial Inclusion Database, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 35.66 | 0.84 | ||

| Per cent of individuals that save at a financial institution [6%] | World Bank Financial Inclusion Database, 2017 | Sweden | 75.43 | 0.12 | ||

| Percentage difference between female and male who have borrowed from a financial institution a, c [6%] | World Bank Financial Inclusion Database, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0 | 0.68 | ||

| Percentage difference between female and male who have saved at a financial institution a, c [6%] | World Bank Financial Inclusion Database, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0 | 0.74 | ||

| Labour force participation rate [6%] | ILOSTAT, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 73.20 | 34.10 | ||

| Percentage difference in labour force participation rate of men and women a, c [6%] | ILOSTAT, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0 | 0.79 | ||

| Opportunities for youth [33%] | Median age [17%] | UN-DESA, World Population Prospects, 2020 | Japan | 48.36 | 19.45 | |

| Harmonised test scores [17%] | Human Development Index, 2018 | Japan | 563.36 | 355.99 | ||

| Perception of quality of education system (1 = worst, 7 = best) [17%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | United States of America | 5.62 | 2.14 | ||

| Hiring and firing flexibility [17%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 5.65 | 2.37 | ||

| Unemployment rate a (15+) [8%] | ILOSTAT, 2019 | Czech Republic | 1.93 | 30.80 | ||

| Percentage difference between youth (15-24) and adult (25+) unemployment rates a, c [8%] | ILOSTAT, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0 | 0.80 | ||

| Per cent of individuals with a bank account [8%] | World Bank Financial Inclusion Database, 2017 | Sweden | 99.74 | 0.40 | ||

| Percentage difference between number of youth (15-24) and adults(15+) with a bank account a, c [8%] | World Bank Financial Inclusion Database, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0 | 0.78 | ||

| Regional disparities [33%] | Quality of transport and trade related infrastructure (1 = worst, 5 = best) [13%] | World Bank Logistics Performance Index (LPI) 2018 | Germany | 4.44 | 1.96 | |

| Access to computer a [13%] | EBRD, LITS, 2016 | Germany | 0.25 | 0.79 | ||

| Access to internet a [13%] | EBRD, LITS, 2016 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0.26 | 0.86 | ||

| Access to water a [13%] | EBRD, LITS, 2016 | Germany* | 0.00 | 0.97 | ||

| Percentage of establishments with checking or savings account a [13%] | World Bank/EBRD BEEPS, 2016 | Russia | 0.00 | 0.45 | ||

| Quality of administrative, health and education systems a [13%] | EBRD, LITS, 2016 | Uzbekistan | 1.25 | 3.05 | ||

| Household head labour market status (worked in the last 12 months) a [13%] | EBRD, LITS, 2016 | Czech Republic | 0.39 | 0.71 | ||

| Completed education of the household head in working age (25-65) a [13%] | EBRD, LITS, 2016 | Estonia | 0.07 | 0.87 | ||

| RESILIENT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier economy | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| Energy sector resilience [30%] | Liberalisation and market liquidity [50%] | Sector restructuring, corporatisation and unbundling (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [33%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | Germany* | 0.67 | 0 |

| Fostering private sector participation (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [33%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | United States of America* | 0.67 | 0 | ||

| Tariff reform (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [33%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | Czech Republic* | 0.67 | 0 | ||

| System connectivity [20%] | Domestic connectivity (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [35%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | Czech Republic* | 0.67 | 0.09 | |

| Inter-country connectivity (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [65%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | Germany* | 0.67 | 0 | ||

| Regulation and legal framework [30%] | Development of an adequate legal framework (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [50%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | Czech Republic* | 0.67 | 0 | |

| Establishment of an empowered independent energy regulator (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [50%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | Czech Republic* | 0.67 | 0 | ||

| Financial stability [70%] | Banking sector health and intermediation [65%] | Capital adequacy ratio [9%] | IMF Financial Soundness Indicators (FSI), IMF Article IV, IHS Markit, National Authorities, Fitch – Sovereign Data Comparator, EBRD FI Risk Reports, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0.29 | 0.06 |

| Return on assets [9%] | IMF FSI, IMF Article IV, IHS Markit, National Authorities , Fitch – Sovereign Data Comparator, EBRD FI Risk Reports, 2019 | Ukraine | 3.12 | -12.47 | ||

| Loan to deposits ratio c [9%] | IMF FSI, IMF Article IV, IHS Markit, National Authorities, Fitch – Sovereign Data Comparator, EBRD FI Risk Reports, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 1 | 0.33 | ||

| Non-performing loans (NPLs) to total gross loans (per cent) a [9%] | IMF FSI, IMF Article IV, IHS Markit, National Authorities, Fitch – Sovereign Data Comparator, S&P BICRA, EBRD FI Risk Reports, 2019 | Canada* | 0.41 | 54.54 | ||

| Loan loss reserves to NPLs (Provisions to NPLs) b [9%] | IMF FSI, IHS Markit, National Authorities, EBRD FI Risk Reports, 2019 | North Macedonia* | 100 | 15.14 | ||

| Asset share of five largest banks a [9%] | World Bank Global Financial Development Database (GFDD), IMF FSSA, EBRD FI Risk Reports, 2019 | Albania | 41.75 | 100 | ||

| Asset share of private banks [9%] | World Bank GFDD, EBRD FI Risk Reports, IMF Article IV, IMF FSSA, Bank Focus, 2019 | Canada* | 100 | 0 | ||

| Financial sector assets c (per cent of GDP) [9%] | IMF FSI, EBRD, Internal Sovereign Risk Report, Bank Focus, National Authorities, IHS Markit, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 100 | 28 | ||

| Credit to private sector c (per cent of GDP) [9%] | World Bank GFDD, S&P BICRA, IMF Article IV, WDI, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 80 | 4.02 | ||

| Foreign currency-denominated loans a (per cent of total loans) [9%] | IMF FSI, IMF Article IV, IHS Markit, National Authorities, 2019 | United States of America* | 0 | 100 | ||

| Liquid assets to short-term liabilities (per cent) [9%] | IMF FSI, World Bank GFDD, IMF Article IV, National Authorities, EBRD FI Risk Overview, 2019 | Russia | 180.62 | 15.54 | ||

| Alternative sources of funding [12%] | Other Financial Corporation’s assets b (per cent of GDP) [50%] | IMF FSI, World Bank GFDD, IMF Article IV, National Authorities, EBRD FI Risk Overview, IMF FSSA, AFDB, 2018 | Canada* | 100 | 0.32 | |

| Stock market capitalisation b (per cent of GDP) [50%] | World Bank WDI, IMF FSSA, IMF FSI, 2018 | United States of America* | 79.24 | 0 | ||

| Regulation governance and safety nets [24%] | Is there a well-functioning deposit insurance scheme? (1 = worst, 10 = best) [25%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | Czech Republic* | 10 | 1 | |

| Do the banks have good risk management and corporate governance practices? (1 = worst, 10 = best) [25%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | Czech Republic* | 10 | 1 | ||

| Is there an adequate legal and regulatory framework in place? (1 = worst, 10 = best) [25%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | Czech Republic* | 10 | 1 | ||

| Is the supervisory body independent and competent? (1 = worst, 10 = best) [25%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | Czech Republic* | 10 | 1 | ||

| INTEGRATED | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier economy | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| External integration [50%] | Trade openness [33%] | Total trade volume (per cent of GDP, five-year moving average) [50%] | World Bank, WDI, 2019 | Slovak Republic | 185.91 | 27.23 |

| Number of Regional Trade Agreements [17%] | World Trade Organization (WTO), 2019 | Germany* | 44 | 1 | ||

| Binding overhang ratio a, b (%) [17%] | WTO, 2018 | Germany* | 0 | 46.30 | ||

| Number of non-tariff measures a [17%] | WTO, 2018 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0 | 4,673 | ||

| Investment openness [33%] | FDI net inflows (per cent of GDP, five-year moving average) [50%] | IMF, International Investment Position Statistics, 2019 | Cyprus | 0.10 | -0.02 | |

| Number of bilateral investment agreements [25%] | UNCTAD, 2019 | Germany | 183 | 8 | ||

| FDI Restrictiveness indicator a [25%] | OECD, 2018 | Slovenia | 0.01 | 0.24 | ||

| Portfolio openness [33%] | Non-FDI inflows (per cent of GDP, five-year moving average) [50%] | IMF, International Investment Position Statistics, 2019 | Cyprus | 0.06 | -0.05 | |

| Financial openness index (Chinn-Ito) [50%] | Chinn-Ito webpage, 2017 | Germany* | 2.35 | -1.92 | ||

| Internal integration [50%] | Domestic transport [33%] | Road connectivity a [25%] | EBRD assessment, 2019 | United States of America | 107.53 | 309.27 |

| Quality of non-road transport infrastructure [25%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2019 | Japan | 89.92 | 24.25 | ||

| Competence and quality of logistics services (1 = worst, 5 = best) [13%] | World Bank, LPI database, 2018 | Germany | 4.31 | 1.96 | ||

| Tracking and tracing of consignments (1 = worst, 5 = best) [13%] | World Bank, LPI database, 2018 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 4.38 | 1.84 | ||

| Timeliness of shipments (1 = worst, 5 = best) [13%] | World Bank, LPI database, 2018 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 4.45 | 2.04 | ||

| Proportion of products lost to breakage or spoilage during shipping a [13%] | World Bank/EBRD BEEPS, 2018-20 | Estonia | 0 | 2.20 | ||

| Cross-border transport [33%] | Quality of customs and border management, trade and transport infrastructure and ease of arranging shipments (1 = worst, 5 = best) [50%] | World Bank, LPI database, 2018 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 4.14 | 1.95 | |

| Cost of trading across borders [50%] | World Bank, Doing Business, 2020 | France* | 100 | 49.79 | ||

| Energy and ICT [33%] | Quality of electricity supply (1 = worst, 7 = best) [25%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 6.78 | 1.65 | |

| Electric power transmission and distribution losses as percentage of domestic supply a [13%] | IEA, 2019 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 2.34 | 23.73 | ||

| Time required to get electricity a (days) [13%] | World Bank, Doing Business, 2020 | Germany | 28 | 267 | ||

| Broadband subscription (per 100 habitants) [13%] | International Telecommunications Union (ITU), 2018 | France | 44.78 | 0.07 | ||

| Number of internet users (per cent of population) [13%] | ITU, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 95.51 | 17.99 | ||

| Level of competition for internet services (50 = monopoly, 75 = partially competitive, 100 = competitive) [6%] | World Bank, The Little Data Book 2017 | United States of America* | 100 | 50 | ||

| Mobile broadband basket price a [6%] | ITU, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2020 | 0.22 | 5.38 | ||

| International internet bandwidth per internet user [6%] | ITU, 2018 | Sweden* | 253,090 | 0 | ||

| 3G coverage (per cent of population) [6%] | ITU, 2017 | Sweden* | 100 | 94 | ||

* Additional economies are at the frontier. Further information is available on request.

a Inverted before normalisation.

b Capped at frontier.

c Mirrored from frontier.

References

S. Adjémian, C. Cahn, A. Devulder and N. Maggiar (2007)

“Variantes en Univers Incertain”, Économie et Prévision, Special Issue.

G. Barlevy (2003)

“Credit Market Frictions and the Allocation of Resources Over the Business Cycle”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 50, pp. 1795–1818.

M. Bertrand and F. Kramarz (2002)

“Does Entry Regulation Hinder Job Creation? Evidence from the French Retail Industry”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 117, pp. 1369-1413.

R. Bouis, O. Causa, L. Demmou, R. Duval and A. Zdzienicka (2012)

“The Short-Term Effects of Structural Reforms: An Empirical Analysis”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 949.

R. Bouis, R. Duval and J. Eugster (2020)

“How fast does product market reform pay off? New evidence from non-manufacturing industry deregulation in advanced economies”, Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol. 48, pp. 198-217.

M. Cacciatore, R. Duval, G. Fiori and F. Ghironi (2016)

“Market Reforms in the Time of Imbalance”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 72, pp. 69-93.

D. Ciriaci (2014)

“Business Dynamics and Red Tape Barriers”, Economic Paper No. 532, European Commission.

E. Dabla-Norris, S. Guo, V. Haksar, M. Kim, K. Kochhar, K. Wiseman and A. Zdzienicka (2015)

“The New Normal: A Sector-Level Perspective on Productivity Trends in Advanced Economies”, IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/15/03.

R. Duval and D. Furceri (2018)

“The Effects of Labor and Product Market Reforms: The Role of Macroeconomic Conditions and Policies”, IMF Economic Review, Vol. 66, No. 1, pp. 31-69.

R. Faini, J. Haskel, G.B. Navaretti, C. Scarpa and C. Wey (2006)

“Contrasting Europe’s Decline: Do Product Market Reforms Help?”, in T. Boeri, M. Castanheira, R. Faini and V. Galasso (eds.), Structural Reforms Without Prejudices, Oxford University Press.

Y. Lee and T. Mukoyama (2015)

“Entry and Exit of Manufacturing Plants over the Business Cycle”, European Economic Review, Vol. 77, pp. 20-27.

A. Sánchez, A. de Serres and N. Yashiro (2016)

“Reforming in a difficult macroeconomic context: A review of the issues and recent literature”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 1297.