State banks on the rise

State-owned banks have grown in importance across the EBRD regions over the last decade. They have become serious competitors for privately owned lenders, expanding both their assets and their branch networks. Many state banks apply less stringent lending standards, operate with smaller net interest margins and accept higher levels of non-performing loans. This greater appetite for risk allows them to soften the impact that economic shocks have on households, small businesses and entire regions. At the same time, while state banks may help to reduce economic fluctuations, their growing importance may come at a cost, resulting in a decline in firm-level innovation and lower aggregate productivity. This partly reflects state banks’ susceptibility to political interference, which can result in credit flowing to less productive firms. Improving the corporate governance of state banks can reduce the risk of such distortions somewhat.

Introduction

The regions where the EBRD invests have traditionally had strong state-owned financial institutions.1 Central Europe and the economies of the former Soviet Union began the 1990s with banking sectors that were dominated by state banks – a legacy of the large monobank systems that had been in place prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall. While many of those state lenders were soon privatised, often ending up in the hands of foreign strategic investors, a number of large banks have remained in state ownership (either in full or in part). Examples of such banks include Sberbank and VTB in Russia, NLB in Slovenia and PKO in Poland. Moreover, in the wake of the global financial crisis, some private banks were (at least temporarily) brought back into state hands, with such developments being observed in countries such as Poland, Hungary and Ukraine. At the same time, entrenched state banks such as National Bank of Egypt and Ziraat Bank have remained powerful players in the southern and eastern Mediterranean (SEMED) region and Turkey. Meanwhile, a number of state banks have recently expanded their operations abroad, with prominent examples including Russian-owned VTB’s operations in Ukraine, Dubai-owned Denizbank in Turkey (which was previously owned by Russian state bank Sberbank), and Sberbank’s ownership of Volksbank, which operates across much of central and eastern Europe.

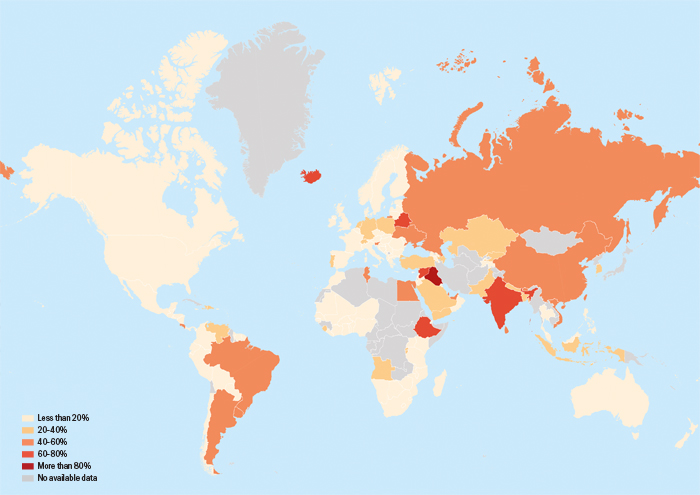

Source: World Bank (Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey) and authors’ calculations.

Note: This map shows the percentage of total banking assets that were owned by state banks in 2016. This map is used for data visualisation purposes only and does not imply any position on the legal status of any territory.

State banks as competitors

The growth of state banks

In Russia, state banks (especially Sberbank and VTB) owned more than 60 per cent of all banking assets in 2016-18 (see Chart 3.2, which combines estimates from the World Bank’s Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey with estimates obtained by aggregating bank-level data from Bankscope and Orbis for 2016 and 2018), with somewhat lower levels being observed in eastern Europe and the Caucasus (EEC). In the SEMED region and Turkey, around a third of banking assets remain in state hands, with much lower percentages being observed in central Europe and the Baltic states (CEB) and south-eastern Europe (SEE). In central and south-eastern Europe, governments privatised most state banks in the early 1990s (with the exception of a handful of large banks in a few countries) and sold them to foreign strategic investors.

Banks’ perception of state banks as competitors

The rapid expansion of state banks’ assets and branches in the wake of the global financial crisis has probably solidified their position as strong competitors in the credit market. In order to assess the extent to which state banks have indeed become stronger competitors, this chapter uses data derived from the second round of the EBRD’s Banking Environment and Performance Survey (BEPS II). As part of BEPS II, face-to-face interviews were conducted with the chief executive officers (CEOs) of 611 banks in 32 countries across the EBRD regions in 2012. That second survey round included a special module looking at the competitive banking landscape in the bank’s country of incorporation, which asked CEOs about the extent to which state banks were strong competitors in various segments of the credit market, both before the global financial crisis (in 2007) and afterwards (in 2011).11

State banks’ strategies

How exactly did state banks step up their activities in the aftermath of the global financial crisis? BEPS II provides unique insight into the main perceived constraints that banks face when trying to acquire new clients, as well as the strategies used to attract new customers before and after the crisis.

Source: World Bank (Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey and World Development Indicators), Bureau van Dijk (Bankscope and Orbis databases) and authors’ calculations.

Note: This chart shows the percentage of total banking assets that are owned by domestic state banks, weighted by GDP. The bar showing 2016 World Bank data for Central Asia has been omitted owing to a lack of available information. The presence of state banks as captured by World Bank data and Bankscope/Orbis data may differ as a result of small differences in coverage and definitions.

Source: World Bank (Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey and World Development Indicators) and authors’ calculations.

Note: This chart shows the percentage of total banking assets that are owned by domestic state banks, weighted by GDP. The sample is restricted to a set of countries for which data are available for 2001, 2008 and 2016.

Source: Bureau van Dijk (Bankscope and Orbis databases) and authors’ calculations.

Note: This sample is restricted to banks with at least 10 years of data on total assets over the period 2004-14.

Source: BEPS II, BEPS III and authors’ calculations.

Note: Data for 2020 are not yet available for Russia or the SEMED region. SEE data do not include Cyprus, Greece or Kosovo, and SEMED data do not include Lebanon or the West Bank and Gaza.

Source: BEPS II and authors’ calculations.

Note: This chart shows the percentage of banks that regard state-owned banks as strong competitors in the SME lending market.

Source: BEPS II and authors’ calculations.

Note: These data represent estimated coefficients for a state bank dummy that are derived from bank-level linear probability models with region fixed effects. The dependent variable is a dummy variable that is equal to 1 if a particular client-related constraint is reported as being a frequent or very frequent reason for rejecting loan applications submitted by large firms (and 0 otherwise). 90 per cent confidence intervals are shown.

Source: BEPS II and authors’ calculations.

Note: These data represent estimated coefficients for a state bank dummy that are derived from bank-level linear probability models with region fixed effects. The dependent variable is a dummy variable that is equal to 1 if a particular strategy is reported as being important or very important for attracting new clients to the bank (and 0 otherwise). *, ** and *** denote values that are statistically significant at the 10, 5 and 1 per cent levels respectively.

The financial performance of state banks

How has state banks’ stronger growth in the post-crisis period affected their financial performance, given that state banks expanded by applying less stringent screening mechanisms and participating more in government lending programmes? In order to answer that question, regression analysis can be used to relate various indicators of bank performance over the period 1999-2019 to the bank’s performance in the previous year, the bank’s ownership status (state-owned or private), country-year fixed effects taking into account changes in the economic outlook of the country where the bank operates, bank capitalisation in the previous year, the ratio of bank deposits to total liabilities, the ratio of net loans to assets, and the lagged dependent variable. Excluding various covariates, some of which may themselves be a result of state ownership, does not change the results in a material way. The sample includes commercial banks, cooperative banks, multilateral government banks, and specialist government credit institutions with assets of at least US$ 2.5 billion.

| Time period | 1999-2007 | 2010-19 | 1999-2007 | 2010-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: | Return on average assets (%) | Net interest margin (%) | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| State bank | -0.415*** | -1.070*** | 0.135 | -0.198*** |

| (0.156) | (0.383) | (0.145) | (0.073) | |

| Lagged bank controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.313 | 0.228 | 0.720 | 0.755 |

| Number of observations | 1,929 | 2,952 | 1,925 | 2,946 |

| Number of banks | 275 | 349 | 275 | 348 |

| Dependent variable: | Ratio of NPLs to gross loans (%) | Ratio of non-interest expenses to average assets (%) | ||

| (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| State bank | 0.291 | 1.558** | -0.073 | 0.030 |

| (0.408) | (0.605) | (0.268) | (0.387) | |

| Lagged bank controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.727 | 0.738 | 0.524 | 0.399 |

| Number of observations | 853 | 2,616 | 1,925 | 2,952 |

| Number of banks | 202 | 337 | 275 | 349 |

SOURCE: Bureau van Dijk (Bankscope and Orbis databases) and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: These coefficients are derived from bank-level ordinary least squares models with standard errors clustered at bank level. *, ** and *** denote values that are statistically significant at the 10, 5 and 1 per cent levels respectively.

State banks and financial stability

The regression analysis also confirms that private banks’ annual credit growth declined substantially during the global financial crisis relative to the pre-crisis period (see Chart 3.9). The sharpest decline was observed in 2009, when credit granted by domestic private banks declined by 32 per cent year on year. While foreign private banks’ credit growth weakened in the midst of the crisis, persistent negative growth only occurred in the period 2010-11, when the euro area sovereign debt crisis intensified.

Source: Bureau van Dijk (Bankscope and Orbis databases) and authors’ calculations.

Note: These coefficients are derived from bank-level ordinary least squares models regressing annual credit growth on various controls, with standard errors clustered at bank level. The coefficients correspond to interaction terms combining private bank and state bank dummies with a crisis dummy. Controls include lagged total assets, lagged capitalisation, lagged ratio of deposits to liabilities, lagged ratio of net loans to assets, lagged return on average equity, lagged annual net loan growth, lagged GDP per capita growth and country fixed effects. 90 per cent confidence intervals are shown.

Source: BEPS II, Eurostat, regional statistical offices and authors’ calculations.

Note: This sample comprises subnational regions in 15 countries: Albania, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Turkey and Ukraine.

| 2010 survey round | 2016 survey round | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: | Crisis impact | Trust in banks | Trust in banks |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Presence of state banks | -0.049*** | -0.085 | 0.909*** |

| (0.014) | (0.197) | (0.280) | |

| Impact of crisis | -1.075*** | ||

| (0.258) | |||

| Presence of state banks X impact of crisis | 1.396* | ||

| (0.698) | |||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.130 | 0.111 | 0.072 |

| Number of observations | 29,620 | 27,244 | 37,775 |

SOURCE: BEPS II, Life in Transition Survey (2010 and 2016 rounds) and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: These estimates are based on linear models that regress an index measuring the impact of the crisis on each household on various control variables using population weights. Standard errors (reported in parentheses) are clustered at country level. Control variables include age, employment status (employed or unemployed), education, income, gender, location (rural or urban), and distance to the capital. *, ** and *** denote values that are statistically significant at the 10, 5 and 1 per cent levels respectively.

State banks and firm-level productivity

The increased role of state banks in the period since the global financial crisis can also be seen in their lending to firms across the EBRD regions. In particular, the results of the Enterprise Survey conducted by the EBRD, the EIB and the World Bank show a widespread increase in the proportion of firms that obtained their last loan from a state bank (as a percentage of all firms that have recently been granted a loan; see Charts 3.11 and 3.12). Those data are derived from the fifth and sixth rounds of the Enterprise Survey, which were conducted in 2011-14 and 2018-20 respectively. In 2018-20, the percentage of firms borrowing from state banks was particularly high in Belarus (70 per cent), Egypt (63 per cent), Russia (54 per cent), Uzbekistan (51 per cent), Ukraine (50 per cent) and Poland (44 per cent).

Economy-wide distortion by state banks

These results also suggest that an increase in state banks’ presence in a region can impede the efficient reallocation of labour and physical capital across firms. This can, in turn, have a negative impact on the aggregate productivity growth of that region as employees and machinery become “trapped” in relatively unproductive firms.24 When this happens, there tends to be a greater dispersion of productivity levels across firms within narrowly defined industries, as unproductive firms propped up by cheap bank credit neither catch up with their peers nor go out of business.

State banks and state-owned enterprises

State banks may play a special role in the funding of other state-owned enterprises. For instance, a recent analysis of China’s 2009-10 economic stimulus plan found that credit expansion had disproportionately favoured state-owned enterprises and firms with a lower marginal product of capital, reversing the reallocation of capital to private firms that had characterised China’s strong growth prior to 2008.28

Source: Enterprise Survey and authors’ calculations.

Note: The figures in this chart are calculated as a percentage of all firms that received a loan in the period in question. Red arrows indicate economies where the percentage was higher in 2018-20 than it had been in 2011-14; blue arrows indicate countries where it was lower in 2018-20 than it had been in 2011-14.

Source: Enterprise Survey and authors’ calculations.

Note: The figures in this chart are calculated as a percentage of all firms that received a loan in the period in question.

Source: Enterprise Survey, BEPS II and authors’ calculations.

Note: These estimates are derived by regressing a dummy indicating whether a firm borrows from a state bank on various controls and country-industry fixed effects. Covariates that are not statistically significant are not shown. The 90 per cent confidence intervals shown are based on standard errors clustered at country level.

Source: Enterprise Survey, BEPS II and authors’ calculations.

Note: These coefficients are derived from a two-stage least squares model regressing various measures of firm level performance (indicated on the vertical axis) on borrowing from a state bank. Borrowing from a state bank is instrumented using state banks’ regional presence. Firm-level controls include country-industry fixed effects, the logarithm of firm age, the logarithm of sales three years previously, the logarithm of employment three years previously, and dummy variables indicating whether a firm is foreign-owned, an exporter, audited, female-owned, politically connected or located in a city with a population of more than 50,000. The 90 per cent confidence intervals shown are based on standard errors clustered at country level.

Source: Enterprise Survey, BEPS II and authors’ calculations.

Note: This chart shows the results of analysis regressing the dispersion of a revenue-based measure of total factor productivity (for manufacturing firms) on a measure of the presence of state banks, controlling for country fixed effects. The line shows the corresponding linear relationship. Each dot represents a particular region. Regions with fewer than 10 manufacturing firms have been excluded.

Source: Bureau van Dijk (Orbis database), World Bank (Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey) and authors’ calculations.

Note: These estimates are derived from an ordinary least squares model which regresses the debt-to-asset ratio on a dummy variable denoting state ownership of the firm and an interaction term combining that dummy with state banks’ share of total banking assets, as well as various firm-level characteristics. The 95 per cent confidence intervals shown are based on standard errors clustered at firm level.

Improving the corporate governance of state banks

Improving the corporate governance of state banks and increasing their commercial focus may reduce the risk of distortion in the allocation of credit to firms. Indeed, cross-country evidence shows that state banks that are not subject to political interference tend to perform better than politicised state banks (although still worse than private banks).29 Moreover, in economies with good governance, state banks have the potential to play an even greater role as providers of stable credit in the face of economic shocks.30

Conclusion

State banks have grown in importance in many of the economies in the EBRD regions in recent years. As those state banks have expanded their assets and branch networks, they have become serious competitors for other banks. Their greater appetite for risk can help to soften the impact that adverse economic shocks have on households and firms, and it can also enable small young firms with little collateral to gain access to finance (especially in regions that are traditionally underserved by private banks). However, state banks’ role as a stabilising and inclusive source of finance is likely to come at a cost, resulting in lower levels of innovation and total factor productivity in firms. The evidence presented in this chapter shows that these costs are partly a reflection of political interference in the lending decisions of state banks, particularly around the time of elections.

Reducing political actors’ direct and indirect intervention in the lending decisions of state banks is of paramount importance in order to ensure that lenders pursue commercial objectives. Policymakers can increase the operational independence of state banks by appointing independent board members, selecting senior managers primarily on the basis of commercial criteria, and assessing performance on the basis of a transparent monitoring system. Staffing policies that are independent of civil service regulations can help to prevent the hoarding of labour for political ends, while periodic external audits based on international standards (with results made publicly available) can help to increase transparency. Moreover, where the state owns less than 100 per cent of the bank, it is essential that minority shareholders’ rights are clearly defined and strongly protected.

In the absence of political frictions, policymakers may seek to use state banks’ privileged access to government resources to distribute large funding packages to the real economy in response to a financial or health crisis. It is important that they do so in a way that preserves competition and limits distortion of the funding market, in order to reduce the risk of misallocating labour and capital across firms. Such lending practices can also help to ensure that state banks have a healthy portfolio of borrowers and limit operational losses, thereby continuing to make a profit (at least on a cyclically adjusted basis).

Box 3.1. The “dark side” of state banks

Critics of state banks often cite political interference in the timing and targeting of lending as the main source of distortions in credit markets. In line with that argument about the “dark side” of state banks, a number of studies have documented political credit cycles in specific countries, for instance in Brazil, Germany, India, Pakistan and Russia.34 This box takes a closer look at political credit cycles in Turkey.

Source: Banks Association of Turkey and authors’ calculations.

Note: “Government strongholds” denotes provinces where the party controlling the central government won all three local elections over the period 2004-14. “Opposition strongholds” refers to provinces where opposition parties won all three local elections. Averages are weighted on the basis of provinces’ populations.

Source: Bircan and Saka (2019a) and authors’ calculations.

Note: These estimates are derived from triple difference-in-differences regressions using data on annual bank credit broken down by bank type (state or private) and province. Each plotted coefficient is derived from a single regression; 90 per cent confidence intervals are shown.

| Government stronghold | Opposition stronghold | Difference in means (p-value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (1)-(2) | |

| Percentage of firms that received their last loan from a state bank | 19.00 | 9.00 | 0.008*** |

| Interest rate on last loan from a state bank in per cent | 11.84 | 11.00 | 0.455 |

| Percentage of firms that needed to provide collateral for last loan from a state bank | 48.00 | 70.00 | 0.097* |

| Average perception as to whether access to finance is an obstacle to doing business on a scale of 0 (none) to 4 (severe) | 0.67 | 0.85 | 0.009*** |

SOURCE: Enterprise Survey and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: “Government stronghold” denotes a province where the party controlling the central government won all three local elections over the period 2004-14. “Opposition stronghold” refers to a province where an opposition party won all three local elections. The last column reports the p-value for a two-tailed t-test of differences in the means reported in the first two columns. *, ** and *** denote statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1 per cent levels respectively.

Box 3.2. Looking on the “bright side” of state banks

Small young firms are traditionally the most financially constrained businesses in an economy. They do not yet have a well-established track record with audited financial statements and often lack the collateral that is needed to take out a bank loan. At the same time, small young firms account for a large percentage of employment creation and often introduce the most innovative consumer products. What role can state banks play in helping this dynamic but financially constrained segment of the economy?

Source: Turkish credit registry and authors’ calculations.

Note: This bin scatter plot controls for the year in which the loan was disbursed and the size of the firm.

Source: Turkish credit registry and authors’ calculations.

Note: This bin scatter plot controls for the year in which the loan was disbursed and the size of the firm.

Box 3.3. Correspondent banking under threat

Correspondent banking is an arrangement whereby one bank (the correspondent bank) holds the deposits of other banks (respondent banks) and provides payment and other services to those banks. Correspondent banking is essential for international trade, as it allows importers to make cross-border payments to exporters. Specifically, correspondent banks facilitate payments between the local banks of the importer and the exporter, which do not usually hold accounts with each other. Correspondent banks also participate in bank-intermediated trade finance solutions, which facilitate trade in situations where there is a high probability of payment not being made or goods not being shipped and enforcement is expensive.41

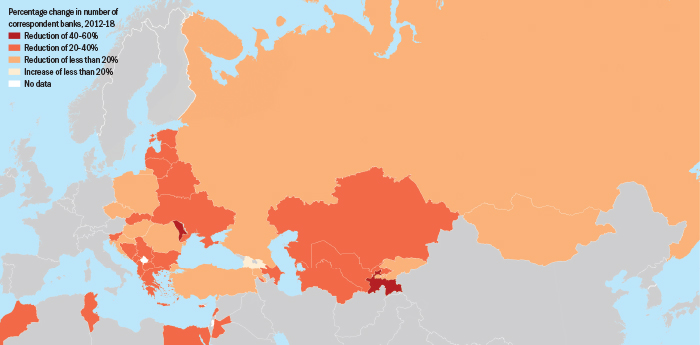

Source: Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

Note: This map shows the percentage change in the number of active correspondent banks in all economies in the EBRD regions between 2012 and 2018 (with the exception of Kosovo and the West Bank and Gaza, for which no data are available). The map is used for data visualisation purposes only and does not imply any position on the legal status of any territory.

References

T. Beck, H. Degryse, R. De Haas and N. Van Horen (2018)

“When Arm’s Length is Too Far: Relationship Banking over the Credit Cycle”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 127, pp. 174-196.

T. Beck, L. Klapper and J.C. Mendoza (2010)

“The typology of partial credit guarantee funds around the world”, Journal of Financial Stability, Vol. 6, pp. 10-25.

D. Berkowitz, M. Hoekstra and K. Schoors (2014)

“Bank privatization, finance, and growth”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 110, pp. 93-106.

A.C. Bertay, A. Demirgüç-Kunt and H. Huizinga (2015)

“Bank Ownership and Credit over the Business Cycle: Is Lending by State Banks Less Procyclical?”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 50, pp. 326-339.

B. Bian, R. Haselmann, V. Vig and B. Weder di Mauro (2017)

“Government ownership of banks and corporate innovation”, mimeo.

C. Bircan and R. De Haas (2020)

“The Limits of Lending? Banks and Technology Adoption across Russia”, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 33, pp. 536-609.

C. Bircan and O. Saka (2019a)

“Lending cycles and real outcomes: Costs of political misalignment”, EBRD Working Paper No. 225.

C. Bircan and O. Saka (2019b)

“Elections and economic cycles: What can we learn from the recent Turkish experience?”, in I. Diwan, A. Malik and I. Atiyas (eds.), Crony Capitalism in the Middle East: Business and Politics from Liberalization to the Arab Spring, Oxford University Press.

BIS (2016)

Correspondent Banking, Basel.

J. Bonin, I. Hasan and P. Wachtel (2005)

“Privatization matters: Bank efficiency in transition countries”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 29, pp. 2155-2178.

M. Brei and A. Schclarek (2013)

“Public bank lending in times of crisis”, Journal of Financial Stability, Vol. 9, pp. 820-830.

D. Carvalho (2014)

“The Real Effects of Government-Owned Banks: Evidence from an Emerging Market”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 69, pp. 577-609.

S. Cole (2009)

“Fixing market failures or fixing elections? Agricultural credit in India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 219-250.

N. Coleman and L. Feler (2015)

“Bank ownership, lending, and local economic performance during the 2008-2009 financial crisis”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 71, pp. 50-66.

L.W. Cong, H. Gao, J. Ponticelli and X. Yang (2019)

“Credit Allocation under Economic Stimulus: Evidence from China”, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 32, pp. 3412-3460.

M. Crozet, B. Demir and B. Javorcik (2020)

“Does Trade Insurance Matter?”, mimeo.

R. Cull and M.S. Martínez Pería (2013)

“Bank Ownership and Lending Patterns during the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis: Evidence from Latin America and Eastern Europe”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 37, pp. 4861-4878.

D. Da Mata and G. Resende (2020)

“Changing the climate for banking: The economic effects of credit in a climate-vulnerable area”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 146.

D. Davydov (2018)

“Does state ownership of banks matter? Russian evidence from the financial crisis”, Journal of Emerging Market Finance, Vol. 17, pp. 250-285.

H. Degryse and S. Ongena (2005)

“Distance, Lending Relationships, and Competition”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 60, pp. 231-266.

R. De Haas, M. Djourelova and E. Nikolova (2016)

“The Great Recession and Social Preferences: Evidence from Ukraine”, Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol. 44, pp. 92-107.

R. De Haas, S. Guriev and A. Stepanov (2020a)

“Government Ownership and Corporate Debt Across the World”, EBRD working paper, forthcoming.

R. De Haas, K. Kirschenmann, A. Schultz and L. Steinruecke (2020b)

“Global payment disruptions and firm-level exports”, mimeo.

R. De Haas, Y. Korniyenko, A. Pivovarsky and T. Tsankova (2015)

“Taming the Herd? Foreign Banks, the Vienna Initiative and Crisis Transmission”, Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 24, pp. 325-355.

R. De Haas, L. Lu and S. Ongena (2020c)

“Close Competitors? On the Causes and Consequences of Bilateral Bank Competition”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 15015.

R. De Haas and P. Tabak (2019)

“The Vienna Initiative: from short-term impact to long-term solutions”, in Ten Years of the Vienna Initiative: 2009-2019: www.eib.org/attachments/efs/10years_vienna_initiative_en.pdf (last accessed on 27 September 2020).

R. De Haas and N. Van Horen (2013)

“Running for the Exit? International Bank Lending During a Financial Crisis”, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 26, pp. 244-285.

R. De Haas and I. Van Lelyveld (2014)

“Multinational Banks and the Global Financial Crisis: Weathering the Perfect Storm?”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Supplement 1 to Vol. 46, pp. 333-364.

B. Demir and B. Javorcik (2020)

“Trade finance matters: Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, forthcoming.

I.S. Dinç (2005)

“Politicians and Banks: Political Influences on Government-Owned Banks in Emerging Markets”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 77, pp. 453-479.

A. Dixit and J. Londregan (1996)

“The determinants of success of special interests in redistributive politics”, The Journal of Politics, Vol. 58, pp. 1132-1155.

F. Englmaier and T. Stowasser (2017)

“Electoral Cycles in Savings Bank Lending”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 15, pp. 296-354.

S. Farazi, E. Feyen and R. Rocha (2011)

“Bank Ownership and Performance in the Middle East and North Africa Region”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5620.

Z. Fungáčová, R. Herrala and L. Weill (2013)

“The influence of bank ownership on credit supply: Evidence from the recent financial crisis”, Emerging Markets Review, Vol. 15, pp. 136-147.

Z. Fungáčová, K. Schoors, L. Solanko and L. Weill (2020)

“Political cycles and bank lending in Russia,” BOFIT Discussion Papers 8/2020, Bank of Finland, Institute for Economies in Transition.

G. Gopinath, S. Kalemli-Ozcan, L. Karabarbounis and C. Villegas-Sanchez (2017)

“Capital Allocation and Productivity in South Europe”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 132, pp. 1915-1967.

B.H. Hall and J. Lerner (2010)

“The Financing of R&D and Innovation”, in B.H. Hall and N. Rosenberg (eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, Vol. 1, Elsevier.

C.-T. Hsieh and P.J. Klenow (2009)

“Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP in China and India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 124, pp. 1403-1448.

G. Jiménez, J.L. Peydró, R. Repullo and J. Saurina (2019)

“Burning Money? Government Lending in a Credit Crunch”, Universitat Pompeu Fabra Working Paper No. 1577.

A. Khwaja and A. Mian (2005)

“Do lenders favor politically connected firms? Rent provision in an emerging financial market”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 120, pp. 1371-1411.

M. Koetter and A. Popov (2020)

“Political Cycles in Bank Lending to the Government”, The Review of Financial Studies, forthcoming.

R. La Porta, F. López-de-Silanes and A. Shleifer (2002)

“Government Ownership of Banks”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 57, pp. 265-301.

M. Mazzucato (2018)

The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs Private Sector Myths, Penguin Books.

A. Micco and U. Panizza (2006)

“Bank Ownership and Lending Behavior”, Economics Letters, Vol. 93, pp. 248-254.

A. Micco, U. Panizza and M. Yañez (2007)

“Bank Ownership and Performance: Does Politics Matter?”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 31, pp. 219-241.

S. Nestor (2018)

“Board Effectiveness in International Financial Institutions: A Comparative Perspective on the Effectiveness Drivers in Constituency Boards”, in P. Quayle and X. Gao (eds.), Good Governance and Modern International Financial Institutions: AIIB Yearbook of International Law, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Beijing.

S. Qi, R. De Haas, S. Ongena and S. Straetmans (2018)

“Move a Little Closer? Information Sharing and the Spatial Clustering of Bank Branches”, EBRD Working Paper No. 223.

P. Sapienza (2004)

“The effects of government ownership on bank lending”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 72, pp. 357-384.

T. Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2013)

“Towards a theory of trade finance”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 91, pp. 96-112.

D.H. Scott (2007)

“Strengthening the governance and performance of state-owned financial institutions”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4321.

E. Sette and G. Gobbi (2015)

“Relationship Lending During a Financial Crisis”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 13, pp. 453-481.

C.-H. Shen and C.-Y. Lin (2012)

“Why Government Banks Underperform: A Political Interference View”, Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 21, pp. 181-202.

A. Shleifer (1998)

“State versus private ownership”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 133-150.

A. Shleifer and R.W. Vishny (1994)

“Politicians and firms”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 109, pp. 995-1025.

J. Stiglitz (1993)

“The role of the state in financial markets”, The World Bank Economic Review, supplement to Vol. 7, pp. 19-52.

J. Tirole (2012)

“Overcoming adverse selection: How public intervention can restore market functioning”, American Economic Review, Vol. 102, pp. 29-59.

World Bank (2013)

Global Financial Development Report: Rethinking the Role of the State in Finance, Washington, DC.

World Bank (2015)

Withdrawal from correspondent banking: Where, why, and what to do about it, Washington, DC.